Call it the next gold, the new oil or the future source of all the world’s geopolitical problems, water is the only natural utility that we ingest. In other words, it’s important no matter from what angle you approach it.

“Water really plays into everything, every sector,” said Francesca McCann of Global Water Strategies, an investment, strategy and policy advisory firm.

It’s becoming an increasingly important focus for Wall Street and investors, though this was not always the case. McCann recalls that she first began her career on Wall Street, most people had not even heard of the “water sector.”

And perhaps that is because most people don’t think water is like oil or other natural commodities, which have value determined by the market.

“The idea is water is free,” said McCann.

Yet the truth is that fresh water is scarce and demand is increasing exponentially, she said.

Commercial enterprises are beginning to understand how costly water is. For them, said Jon Freedman, WG’91, the global government relations leader at GE Water & Process Technologies, the story is not a doom-and-gloom scenario. Big corporations have been placing water issues front and center in their sustainability strategies.

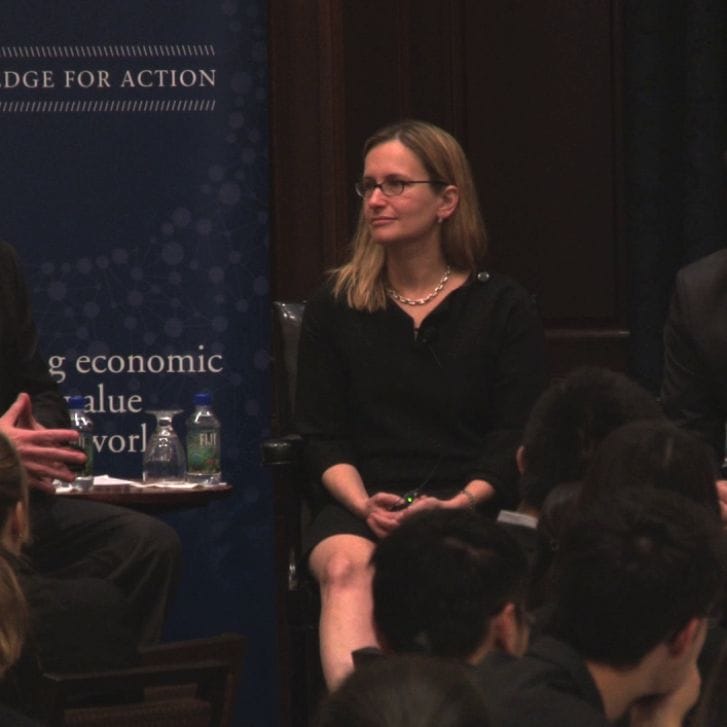

Freedman and McCann spoke at a joint seminar from the Initiative for Global Environmental Leadership (IGEL) and the Institute for Environmental Studies titled “Liquid Gold: Global Water Developments and Opportunities.”

Two of the largest users of water are the agricultural and energy industries. About 60 percent of water-reliant energy generating plants in the world are located in areas already under significant stress, said Freedman. As much as 2 million to 4 million gallons of water are used in your average fracking well.

For the operators of these facilities, not only is the water they insert into their systems valuable, but the water that comes out the other end is as well.

“Waste water is an incredible resource,” Freedman said.

Part of the reason is that the technology to recycle that waste water is far cheaper—25 percent as expensive—as the costs of desalination.

Part of the reason, too, is that value can be mined from the waste water. The “key to the kingdom,” according to Freedman, would be energy recovery and conservation. GE’s goal is to produce a waste-water recovery technology that uses the excess energy in the actual waste water to power itself and be self-sustaining.

Freedman and McCann testified, too, to the opportunities for sustainable careers in the water sector. Unlike when McCann began, major employers on Wall Street and elsewhere (like GE, Goldman Sachs, McKinsey, Bloomberg) now have units dedicated to water, affording interesting Penn grads opportunities to research, invest in and promote water conservation and recycling efforts and technologies.