One anecdote can illustrate why Garrett Moran WG82 went from finance to nonprofit. He recalls doing a mock job interview this spring with a student, Alex—a day-to-day activity that even the president of mentoring company Year Up does and enjoys. Alex showed Moran his resume, which didn’t list a high school. When asked about it, the student confessed that he dropped out of high school at 15 to take care of his father with Alzheimer’s. Alex then trained himself in information technology and launched a part-time computer repair business to help support the family. He was earning $1,000 a week by the age of 16. By 17, his father was in a nursing home, giving him time to earn a GED diploma and a job. Put that on your resume, Moran recommended. Alex hesitated then agreed to, admitting that Year Up made him “ready to take the world on.” He now works as an intern at Google.

Moran was blown away by Alex’s story—and you get the sense that such a mission—helping young adults like Alex—is what maybe Moran dreamed about during his three decades in finance. He devoted 20 years to investment banking at Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette, followed by more than a year at MMC Capital. After that, he says, he was ready to join the nonprofit world full time. He had been on nonprofit boards—like the board of Posse Foundation, where he served for over a decade—and gotten a good window into the lives of children who “lost the ZIP code lottery” and were born into impoverished circumstances. He wanted to serve them further. But then his brother, a journalist, told him he could have far more impact by giving away his money than by becoming a “working stiff” himself inside a nonprofit.

Garrett listened. He looked around at opportunities—seeing charities that were too bloated and bureaucratic or too small and shoestring—and nothing that interested him. He took a job offer to join his former DLJ boss at Blackstone Group as a senior managing director.

After seven years at Blackstone, in 2013 he found the cause — and, just as important, a compelling business approach — that captured his full-time attentions: 15-year-old, Boston-based Year Up that helps “opportunity youth” like Alex launch careers through its demand-driven model.

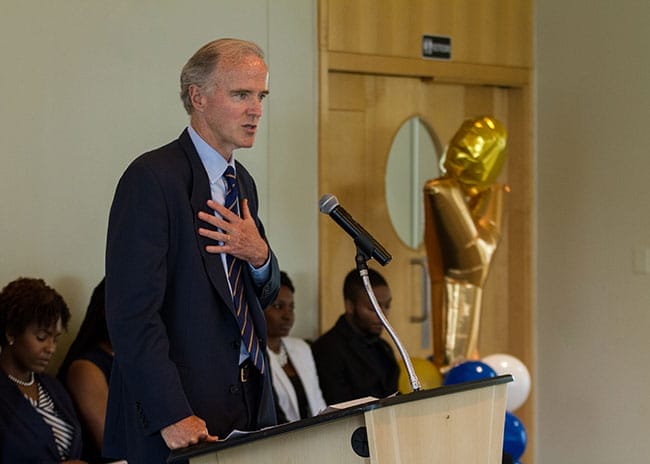

I connected with Moran at the 2015 graduation for Year Up Philadelphia, held on July 14 at the Independence Visitor Center across the street from the Liberty Bell. It was a fitting location for an organization helping individuals realize their American Dream. And it was a lively discussion that ranged from Moran’s career, to his current organization, to his Wharton ties. What follows focused on intriguing differences Moran has noticed between leading in finance and leading in nonprofits.

Nonprofit Leadership Observation #1: Realizing New Power of Old Skills

In finance, Moran possesses skills and leadership that nearly everyone else around him also brought to the table. In the nonprofit world, his skillset was scarce and far more impactful. Applying “commercial common sense,” knowing what risk is worth taking and what audacious goals are achievable are at a premium among nonprofits. Rallying a group around those goals and inspiring people to perform above their own expectations are in equally short supply.

“If you have a diverse business background, you bring a lot to the party,” he says.

Nonprofit Leadership Observation #2: Turn up the Rigor

At Blackstone, as Moran remembers, it was common for colleagues to bring an idea to a meeting with the full expectation that his or her peers would then try to tear it down.

“The nonprofit world doesn’t operate that way,” Moran says.

Now a leader in that nonprofit space, he’s brought a touch of the “adversarial” system to nonprofits—in at least encouraging more vigorous debate and preparation. For instance, when Year Up is exploring opening in a new city, individuals prepare an idea memo to bring before an investment committee, making the case for the move.

Nonprofit Leadership Observation #3: Appreciate Diversity

In finance—where nearly everyone shares educational and professional backgrounds—colleagues and competitors shared a common language and expectations. “You could say things in shorthand,” Moran says.

In the nonprofit sphere, there’s much more diversity of backgrounds, there’s less focus on financial returns and more on social payback.

“It’s a much more verbal environment,” he says.

In that way, Moran has learned to lead with more care, patience, praise and communication. Moran likens the change to a shift in his leadership metabolism.

Watch a 60 Minutes profile from 2014 to learn more about Moran and Year Up’s efforts to build a jobs program that benefits both employers and underprivileged youth.

Year Up aspires to take young men and women from inner-city neighborhoods and guide them toward building a career for themselves. Across 14 cities, the organization selects students—all 18- to 24-year-old high school graduates—who are poised to succeed. They receive six months of classroom training for soft skills and technical skills, then a six-month paid internship through a partnering employer. Within four months of graduating from the program, 30 to 40 percent get hired full time at the internship company and 85 percent are enrolled in college fulltime or working, earning average starting salaries of $35,000.

What differentiates Year Up’s business model—because there are plenty of nonprofits working to mentor youths in the inner-cities—is the investment in job skills, career development and the employer relationships, explains Moran.

“We’re really in our early days … we’re building the foundation of something that’s big,” Moran told Year Up’s Philadelphia graduates.