I was 17 when I arrived at the Philly airport in 1999 with just two suitcases. It was my first time in this country, and I knew no one. I spent the next four years working my way through two undergraduate degrees in one of the most prestigious schools in the world. Fast-forward to today, and I am back, this time to get my MBA from Wharton. Along the way, I met my husband and started a family. We are both Turkish, and our families live in Turkey. So naturally, everyone asks if and when we are planning to go back. We had the same answer for a while: We have a 10-year plan and we will re-evaluate then. As years passed, what we noticed was that the 10-year plan never shrunk into a nine-year plan, an eight-year plan, a seven-year plan; it was always the 10-year plan. However, in the last couple of years I noticed that we don’t give this answer anymore. It seemed like we had abandoned the 10-year plan. I wondered why recently.

Did we grow up to realize that we were foreigners to our own country because we had been in the U.S. for almost 15 years now? Or was it that our jobs had become so “unportable” that our lives and education were worth so much more here? The answer is none of the above. Unfortunately, the issue runs much deeper than that. In the last 10 years, we had the chance to watch Turkey as it became a secular model of the Middle East.

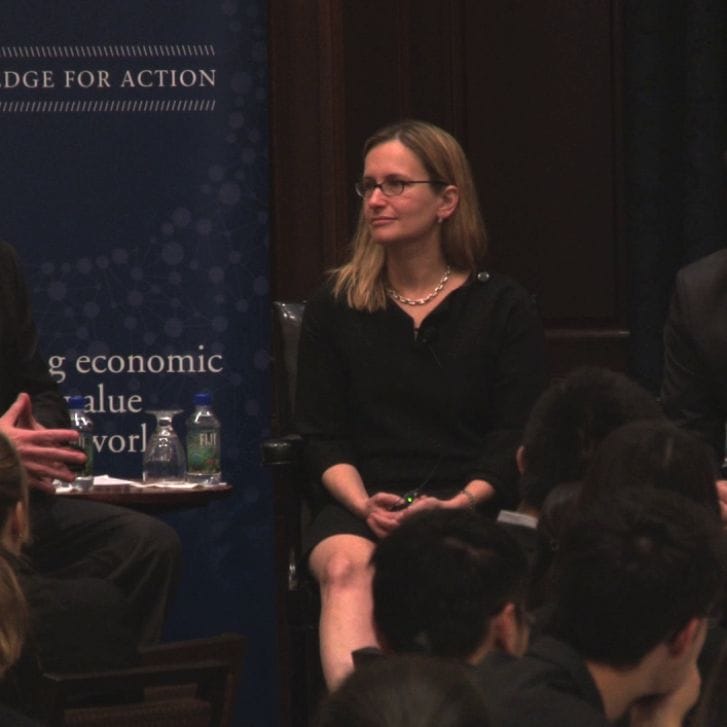

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Photo credit: World Economic Forum.

The Turkey of our youth was paralyzed by their coalition governments’ inability to achieve any economic progress and high inflation. Things started to change with the election of the AKP, the party of current Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Under AKP rule the economy boomed. However, the pillars of secular institutions were also changing. Liberties eroded. A partial ban on alcohol sales was imposed, the government encouraged women to have at least three children and stay at home (read more about Erdogan’s stances and public statements on the role of women), and couples kissing in public were admonished. In 10 years, Turkey surpassed China in the number of jailed journalists. The Dogan Group, Turkey’s biggest media conglomerate, was fined an unprecedented $2.5 billion in 2009 for alleged tax evasion.

When police brutally intervened against a handful of peaceful protestors in June 2013, thousands of outraged citizens poured down to the streets calling for Erdogan to resign. I happened to be in Turkey then. I wasn’t on the streets protesting, but I watched my friends and family as they posted videos and messages on Twitter and Facebook of themselves being targeted by water cannons and tear gas. In the end, four people were killed and around 5,000 injured.

Turkey is not Egypt. Do not expect a “push” from the army to “help” the democracy. As the prime minister has said, the voters put him where he is now. Erdogan has 50 percent of the votes and 64 percent of the parliament seats. He is not leaving unless voters remove him.

With municipal, parliamentary and presidential elections coming up, the next three years will be critical for Turkey’s long-term prospects. As for me and my family, the Turkey I envision has my son holding his girlfriend’s hand without being harassed, schools that teach critical thinking, and politicians that do not lie and instead protect the rights of its citizens. There is a long road ahead, but hopefully not that long so that we can revisit our 10-year plan soon.