Stanford Business Professor Jonathan Berk and his co-author Jules van Binsbergen have a summary piece on a formal academic paper about investment skill that they published in the Journal of Financial Economics in 2014. Here is a snippet:

“Active fund managers are skilled and, on average, have used their skill to generate about $3.2 million per year. Large cross-sectional differences in skill persist for as long as ten years. Investors recognize this skill and reward it by investing more capital in funds managed by better managers. These funds earn higher aggregate fees, and a strong positive correlation exists between current compensation and future performance.”

This is quite a bold claim, given the seemingly relentless attack on active management the past few years. However, this claim is coming from Jonathan Berk, who is not just another academic—this guy is the real deal. Berk is a very well-known name in academic research circles.

One of his most famous papers, co-authored by Richard Green, is titled, “Mutual Fund Flows and Performance in Rational Markets.” The piece is a must read for anyone making an informed claim that active management is a complete waste of time. The Berk and Green paper made researchers rethink how they determine whether an investment manager’s performance record is due to skill or luck.

Before Berk and Green, researchers testing the efficient market hypothesis pointed toward the evidence that mutual fund manager performance has little persistence. Managers who do well in a specific year, don’t tend to achieve their same “skill” in future years. In other words, skill isn’t persistent. And of course, the “logical conclusion” from this research was that good performance is simply due to luck. Err … wrong.

Investment Skill Versus Luck: It’s Complicated

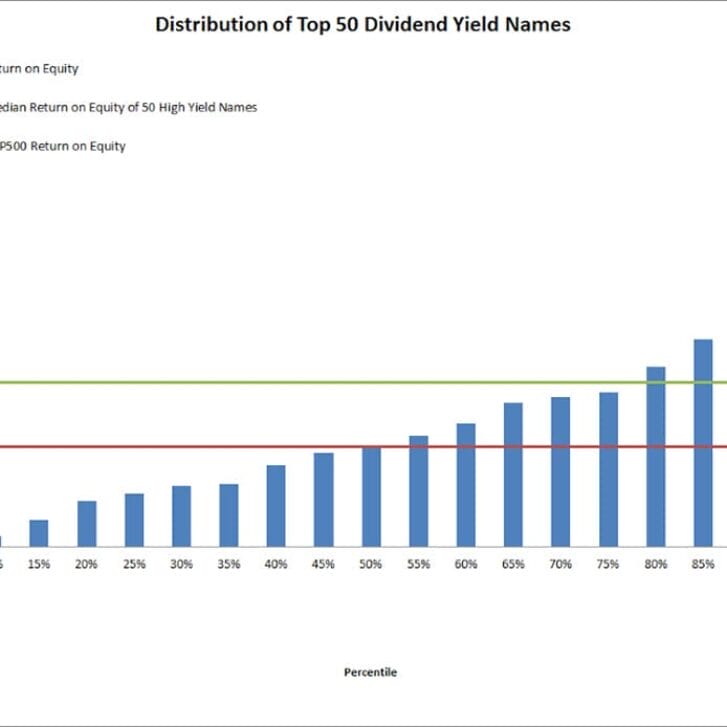

The “big” idea from Berk and Green is that some active managers do have skill; however, asset allocation markets are pretty efficient. The good managers get burdened with too much capital, but that doesn’t mean skilled managers don’t exist!

Consider a manager that can generate $1 million of alpha on a $10 million portfolio, or 10 percent alpha. This manager will quickly get more assets from allocators looking to capture some edge. This same skilled manager may be able to generate $10 million of alpha on a $1 billion portfolio (only 1 percent alpha). So this truly skilled manager will be quickly disregarded as “lucky” because their alpha went from 10 percent per year to 1 percent, and 1 percent per year is hard to distinguish from dumb luck.

Researchers who fail to account for this industry dynamic conclude that skilled active management is not persistent. An analogy is the research we recently highlighted on the “hot hand” in basketball. Research initially concluded that there was no such thing as a hot hand because shooters who got on a streak didn’t maintain their persistent streak. Of course, what happened is that defenders started closely guarding the streaky shooter—equivalent to dumping more assets on an asset manager—and the streaky shooter stopped looking so great. So the basketball player probably was on a streak—and would have continued that streak—but a new burden was placed on the hot-handed player and he was unable to continue being hot.

Watch a video of Berk explaining his insights into the investment skill versus luck debate.

Editor’s note: The original version of this article first appeared on AlphaArchitect.com on June 19, 2015.