I’ve forced myself to the gym after long days in class for three years, but my workouts certainly did not prepare me for an encounter with the boisterous and intelligent David Pottruck, C’70, WG’72. At a school like Penn, it is no surprise to have an opportunity to put an indelible personality and face to a name on one of the campus’ buildings. Among many other acts of generosity, Pottruck has endowed the main student gym. As a junior, meeting the man behind the finance legend is an incomparable way to grasp the path to success.

Pottruck was faced with the unique experience of coming from an analog world and adapting to an Internet-centric workplace. At Charles Schwab, his challenge was to compete with E*Trade, which was founded in 1991 and went public in 1996, growing by offering investors the option to trade online. Pottruck and his team recognized the need to adapt to the way that clients preferred to trade en masse. Charles Schwab had branch networks and call centers, and its team was used to people calling to input the data to make a trade.

“We used to advertise that at $80 per trade, we were 70 percent cheaper than Merril Lynch, and now suddenly we’re the high-price guys,” Pottruck recalled.

To compete with E*Trade, Charles Schwab launched E-Schwab, which was extremely successful at $29.95 per trade. Michael Useem, who was interviewing Pottruck fireside chat-style, noted that E-Schwab launched on January 15, and by December of that year, the market value of the “discount” investment firm of Charles Schwab exceeded Merril Lynch. Schwab and E-Schwab were No. 1 and 2, and E*Trade came in at No. 3. Useem, Wharton’s William and Jacalyn Egan Professor of Management who has taught alongside Pottruck (an adjunct professor) during Wharton Executive Education courses, was not only asking questions but also filling in Pottruck’s accomplishments when the finance legend was too humble to brag.

Getting back to the story, Charles Schwab became one of the successful players in the market during the time of online expansion, in large part because Pottruck had the insight to respond to what the consumer base wanted.

“Customers thought that having a Schwab and E-Schwab account was too complicated. We were getting letters by the hundreds every month,” Pottruck continued.

He and his team believed that for every customer writing them a letter, there were 10 more unhappy customers.

“You don’t build a business on unhappy customers. So we had to make a change [to an affordable, integrated online platform]—which cost us 25 percent of our profits, which meant that everybody had to be on board,” he said.

Though it was tough to learn how to take on such dramatic change, it was the long-run vision of the company that gave Pottruck the foresight to enact such a pioneering program. Getting everyone on board—that was another story entirely. His speechwriter at the time told him that he needed to show who he was to the people he was addressing because “you have to share with the audience why this matters to you, and reveal who you are and talk about yourself in a way that makes you believable and credible.” This way of interacting with his audience, Pottruck told us, has helped him to more effectively communicate his message throughout the years.

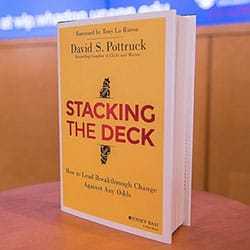

Pottruck, who had long served as Chuck Schwab’s “right-hand man,” went on to serve as co-CEO with the founder from 1998 to May 2003, when Pottruck became sole CEO. In July 2004, the company board ended his role at Charles Schwab after he and Schwab built it into a company with over a $1 trillion in customer assets. Since then, he’s become chairman of HighTower Advisors, a wealth management firm he helped launch in 2008, as well as chairman of CorpU, a leadership training firm. Pottruck serves on Intel’s board. He also recently wrote a book, Stacking the Deck: How to Lead Breakthrough Change Against Any Odds, the reason why he was giving the lecture on campus for Wharton Leadership’s Authors@Wharton Speaker Series.

What stuck with me from his February lecture comes down to this:

Who are you, and why do you care? You have to be willing to reveal yourself to be worthy of trust and commitment.

“LISTEN. Nobody does this well enough. Come to the conversation curious. Don’t let someone talk just to let them talk. I want to know what you have to say. What do you think of that? How did that idea come to you? Really want to listen. Get out of your head and into someone else’s,” was what Pottruck said in his closing remarks.

Though Pottruck’s was a well-wrought path to success, the obstacles he encountered were numerous and challenging. It is often hard to remember that although there are usually many similar factors that contribute to success, each person’s story is a different one. It is so refreshing as an undergrad to hear this unique story of success and to know that believing in your message—and yourself—is half the battle.

I know I am not alone in the Penn community as someone who constantly evaluates her every move, weighing outcomes and others’ influences on whether I should take a risk or not. While it is good to take careful consideration of our actions, sometimes it can be paralyzing to consistently worry about the outcomes of a decision. As we mold ourselves into intelligent and conscious individuals, we might do well to give our gut feeling a chance—if, after careful evaluative reasoning, something feels right to you, it probably is.

Pottruck’s point about communicating this to our audience is crucial: When you believe something wholeheartedly, offer insight into your thought process, your motivations for your decisions and the outcome you are aiming for. This is the most effective way to get people on board with your goals—simply because they want to know who you are and why you are doing what you’re doing. Employers and team members want to see the layers of our commitment to the projects and ideas we propose.

As I enter the stage of my life that requires me to make huge career decisions about how I want to spend every day of my week, how compelled am I to excel and effect change in an industry?

All of us Penn students might consider that the areas in which we will be happiest are those that allow us to use our personal strengths, passions and work ethic. Let us not waste our talents for the sake of the norm but instead follow David’s advice to take the road less travelled and craft a life experience that is true to our convictions.