In the United States alone, the taxi transportation industry has a market of over $11 billion. Rideshare company Uber, with its presence in 43 countries, wants the lion’s share. Uber is leveraging cutting-edge technologies for its operations and billing, as well as dynamically matching supply with demand. Above all, it is persuading policymakers and riders for a big disruption, despite heavy opposition all across the globe. Vancouver, Canada, is the only city in the world where Uber had to abandon its operations.

Traditional taxis are “hail and go,” which means people can stop a taxi on the street and hire it for their short travel. Most cities require a license or permit to operate a taxi within pre-defined city limits; in many North American cities, this permit is also called a medallion. For example, New York City has issued 13,437 medallions, the right to run a yellow taxi. Uber drivers do not need these medallions or permits.

Ever wonder why it is so hard to get a cab when it pours and you need one the most? A study led by the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) has an answer. Researcher Oliver Senn analyzed satellite data on weather conditions over a two-month period, and he obtained 830 million GPS records of 80 million taxi trips. The data shows that it was not the high demand for taxis that resulted in a perceived shortage on rainy days; instead, it appeared that many cabbies simply did not pick up passengers, fearing accidents on the wet roads. With Uber, when you put in your request for a ride, you know for sure whether you will get one or not. Rainy days are not a problem with Uber as it can temporarily increase supply by enticing more drivers with “surge pricing.”

San Francisco-based Uber connects passengers with drivers via mobile apps, and it currently operates in 43 countries. The five-year old company carries a valuation of over $18 billion, which makes it worth more than rental car giants Hertz and Avis combined. Heck, on paper, it is more valuable than Expedia, Hyatt, TripAdvisor, Best Buy, Sony and many more big names! Uber does not carry any tangible inventory, and it is also in the process of expanding its business to logistics (i.e., transporting cargo or freight through a network of independent drivers). Uber teams ingeniously monitor social media to get feedback from their customers in real time, allowing them to make dynamic supply adjustments as needed. Their complex business intelligence systems can learn where riders come from and go to and how these patterns change, depending on the day of week, season, weather, and sporting events or business conferences.

I have taken Uber rides across continents—in Seattle, San Francisco, London, Barcelona and many places in between. My friends, second-year Wharton Executive MBA students Erica Stephens and Sudhanshu Juneja, will tell you that I am so obsessed with the disruption that I talk to drivers in order to know medallion prices across cities, and I watch how those prices go down with the entry of Uber in any new market. Perhaps my ability to speak three languages fluently has helped me to connect with drivers across countries and cultures. An acquaintance of mine in Vancouver owns over five medallions priced around $800,000 each, and I always recommend that he offload at least half of them before Uber succeeds in repenetrating the Vancouver market. Sadly, he has not acted on my advice yet.

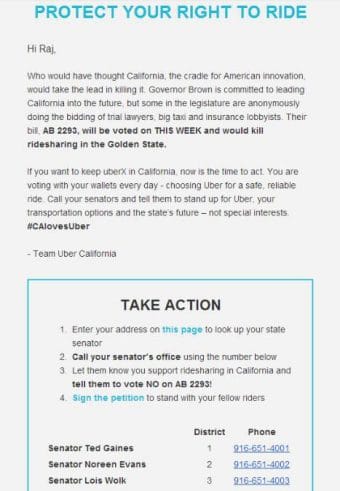

Uber has been heavily criticized for aggressively lobbying, following unfair labor practices, jeopardizing the security of passengers and drivers, and playing with local laws by requiring no permits. Unlike traditional taxi drivers, Uber operators do not have to file for licenses, adhere to fixed rate standards or comply with many other stringent regulations that traditional taxi drivers must follow. Uber accomplishes this by engaging lobbyists and local lawmakers, as well as proactively involving their customers in plethora of petitions. Uber retains the services of the Franklin Square Group, a Washington, D.C.-based technology lobbying firm, to help sway public opinion in the company’s favor. David Plouffe, the former campaign manager and White House adviser to President Barack Obama, has joined Uber as senior vice president of policy and strategy to strengthen this area even further.

“We needed someone who understood politics but who also had the strategic horsepower to reinvent how a campaign should be run—a campaign for a global company operating in cities from Boston and Beijing to London and Lagos,” said Travis Kalanick, Uber CEO.

On the consumer front, Uber uses its horsepower to engage the customers in changing local laws and policies. Here is an email I received from Uber on August 19 requesting me to sign a petition against bill AB 2293 in California and showing my love for #CAlovesUber. For the record, I live in the state of Washington.

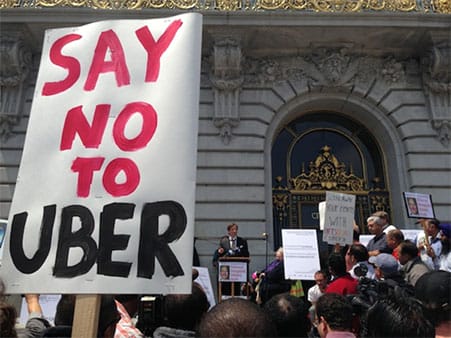

This summer, taxi drivers across Europe vented in protests, blocking traffic in some of the Continent’s largest cities to protest the unfair advantages held by rideshare services that are not subjected to the same fees and regulations as the traditional taxi industry. I witnessed many appeals and posters across the city of London during a visit in September. In my own backyard, Seattle, the City Council originally voted to cap the number of drivers active at any given time on each rideshare system to 150, which means Uber would be allowed 150 drivers at one time, during the day or night. (The same goes for its close competitors Lyft, Sidecar or any other similar transportation network company that decides to set up its operations in the rainy city.)

Taxi union members protest against ride-sharing services like Uber. Photo credit: Chief Organizer Blog.

In response, the ridesharing companies launched a massive public relations campaign and lobbying effort linked to Seattle’s reputation as a center for technology innovation, and they eventually succeeded in lifting the cap for 150 rides.

Uber has also been criticized for “surge pricing,” which supports dynamic pricing and exploits the low-supply situations by charging higher prices. This area is a dream come true for any microeconomics professor, who has been teaching demand-and-supply curves for years but never got to witness the rising dynamic prices in the traditional taxi industry.

Watch a comical video depicting Uber and Lyft competition and inflow of new money.

Bottom-line: There are pros and cons of any new disruption, and Uber is no exception. On one hand, it solves many problems of traditional taxi by leveraging state-of-the-art technology and brings efficiencies to an age-old system; on the other hand, it is being a little socially irresponsible by detaching itself from the contracting drivers and playing ruthlessly with its close competitors. There is also a genuine fear of moving from multiple “local monopolies” to a unified single monopoly or duopoly operating at a global level.

There is no denying that Uber has disrupted an operational model that was hard to crack, and despite all of its problems, it has become a poster child of modern operational innovation. Uber’s strong branding and exploitation of mobile technologies have provided a clean solution to messy transportation problems, and the company’s global expansion in such a short timespan is incredible. There is no stop in sight for Uber. Love it or hate it, this company is here to stay!

Editor’s note: The original version of this post appeared on LinkedIn on Aug. 20, 2014