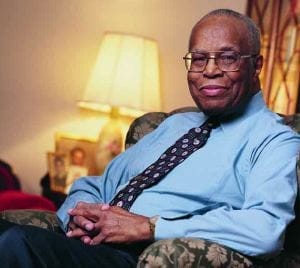

J. Arnett Frisby, Jr., WG’42, reeled in his first job offer when Glen Miller ruled the airwaves and companies still tracked payroll in thick paper volumes. The General Accounting Office offered $2,000 a year, not bad at a time when Frisby – his freshly inked MBA in hand – says a good education guaranteed nothing to an African American. “At that time, it didn’t make any difference if you had a PhD and you were a Negro,” he says, speaking with an accent that reveals a boyhood spent south of the Mason-Dixon line. “Some of the Negro red caps working in the railroad stations were said to have had advanced college degrees.” At Wharton, Frisby had a taste of what life could be when segregation loosened its grip. He felt a certain freedom he missed growing up.

“I could do certain things I couldn’t do in Baltimore. In Baltimore, a lot of the places wouldn’t even wait on you. Some of the women used to go up to Philadelphia to shop.”

To trace Frisby’s professional steps and those of Wharton grads from the last six decades is to step through history. Their stories tell the world’s tale of social struggle, technological revolution, managerial innovation, the spiral into economic chaos, and heady rebirth.

At this spring’s alumni reunion, hundreds will share those experiences. If you can’t make it this May, or if your class isn’t celebrating a reunion this year, maybe these stories will encourage you to come back to campus for the next one.

Here’s a glimpse into the lives of just a few of the University’s well-respected alums, some of whom will be at Penn to mark class reunions this spring. They are Frisby, Wharton’s oldest living African-American alum; Milton Silver, W’52, professor, author, and consultant in management and organizational studies; Thomas E. Haley, WG’62, vice president for market data at the New York Stock Exchange; Stephen Co, WG’72, senior VP at Rabobank in Singapore; Nancy E. Boyer, WG’82, a scholar on emerging democracies; restaurateur Nancy Yaffa, WG’92; and H.S. “Sam” Hamadeh, WG’97, a founder of the online career media company Vault, Inc.

Diversity 101

J. Arnett Frisby, Jr., 85, is the son of an expert auto mechanic and one-time apartment building custodian who learned accounting by taking correspondence courses. He wanted his son to go to Wharton, but he couldn’t afford to send him.

“Being African American, I said, ‘How in the world did he even know anything about Wharton School?’” Frisby wondered.

With his dad’s dreams in mind, Frisby studied history and mathematics at Morgan College (now Morgan State University) in Baltimore. It was actually the State of Maryland’s discriminatory educational policies that punched the young man’s ticket to Wharton. They wouldn’t let him attend the state graduate school with white students, but the state had a program that paid the tuition for African Americans to go elsewhere. Frisby headed to Wharton on Maryland taxpayers’ dime. “They wouldn’t let me into the University of Maryland,” he recalls, “but I got a far better education than I could have gotten there.”

But fulfilling Wharton’s thesis requirement was almost too much. Frisby was supposed to graduate in 1940 and started a thesis about accounting problems faced in personal finance companies like the one his father worked in with two other men. The young MBA seeker read all he could and even traveled to New York where there was a personal finance company run by African Americans. In the end, he scrapped the idea for lack of material, leaving him with no topic and no thesis for graduation. He started over, this time researching accounting for earned surplus. Teaching part-time, he trolled through almost 2,000 corporate reports in a year and finally finished his thesis – for which he was awarded an honorable mention – in time for graduation in 1942.

He married wife Olga and headed to the General Accounting Office.

Frisby eventually was promoted to supervisor after the agency corralled a group of African-American employees into a single unit auditing the U.S. Coast Guard’s payrolls. A black man was allowed to supervise only when the job didn’t include managing white workers.

But Frisby had other ideas for the future. He wanted to return to the college environment – this time as a business and financial administrator and faculty member. He held a series of jobs, beginning with accounting positions at Howard University, and then as comptroller at Morgan State, afterwards landing an assistant professorship at Hampton Institute (now University), where he was also assistant to the business administrator. He then returned to Howard as an assistant for business operations.

Public accounting also interested him. But here again, he ran into the old barrier of race. In those days, people needed experience in the field before they could take the Certified Public Accountant’s exam. No firm would hire Frisby. One interviewer said point-blank that clients wouldn’t want a black man auditing their books. Finally, Frisby returned to government work after his job at Howard was eliminated in reorganization.

For the next three decades, he worked at the Treasury Department’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing, first as an internal auditor, and then as a management analyst involved in the records disposition management program.

Promotions were still hard to come by. “My experience in school, teaching, and working in business and financial offices didn’t seem to count for much,” he recalls. “Some of the white fellows who came in had less experience, and they would move right on up.”

By the time Frisby retired in 1993, the weight of discrimination had eased considerably, but he still believes a subtler form pervades the workplace. He offers one piece of advice to those who have to deal with it: “If a person treats you unfairly or is downright mean, don’t get yourself upset about it. It’s that person’s problem, not yours.” Today, Frisby is retired and living in Annandale, VA. His four children and five grandchildren help keep him young, along with some arthritis medication he credits with letting him dance at alumni functions. He also loves to sing.

And he’s looking forward to his May reunion on campus. “I love people; that’s my biggest enjoyment,” he says.

Managing Change

Milton Silver, WG’52, found his professional calling during his days as an MBA student. (He had already completed an engineering degree at Penn.) His inspiration? Professors who put academic theory into action by consulting with corporations and then brought the results back to the classroom.

“I look back on it, and it seems that very early I had a very clear vision that I wanted to come back and be a professor; and I was going to be a consultant,” Silver says. “I just saw it as the best of both worlds.”

To get his start, he went to work for RCA in New Jersey, a company that had a generous tuition reimbursement program for employees. By day, he worked in Camden; by night, he commuted to New York’s Columbia University, where he worked on his PhD. It took five years to complete the classes called for to become a candidate, and twice that long to finish his doctorate and pay RCA back the additional two years service he owed the firm for paying his way.

To get his start, he went to work for RCA in New Jersey, a company that had a generous tuition reimbursement program for employees. By day, he worked in Camden; by night, he commuted to New York’s Columbia University, where he worked on his PhD. It took five years to complete the classes called for to become a candidate, and twice that long to finish his doctorate and pay RCA back the additional two years service he owed the firm for paying his way.

But at last, in 1962, Silver had the credentials he needed. He taught briefly at Wharton, but then settled in at Drexel University, where he felt he could devote more time to consulting.

Initially, he capitalized on his engineering background, helping companies with their computer-based information systems. The work soon led to staff development projects.

Silver remembers vividly when IBM introduced its 1400 series computers and RCA the 501 in the 1960s. Companies were suddenly able to order raw materials, track sales, deliveries, and accounts payable and receivable all in a single computer system. Previous punch-card computers had been able only to service single departments. The new model forced both employees and employers to adapt.

“There was a considerable amount of training necessary to understand the contribution technology could make,” says Silver, now 72. “People had to learn how to think about their jobs.”

That sort of on-the-job adjustment foreshadowed what Silver believes is the career development model companies should provide today. No modern company can promise a job for life, he says, but they can promise learning that seeds growth for an employee’s future success.

And where Arnett Frisby fought his own personal battle for workplace fairness, pursuing promotion after promotion despite discriminatory employment practices, Silver has worked on the corporate side to help companies stretch their ideas about where and how different types of people fit in. Working with large pharmaceutical firms like the forefathers of GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb, for example, revealed the special challenge of coordinating research and development across the globe.

The basic problem is one Silver has long been familiar with. Recalling his own days at RCA, he recounts a business trip spent trying to stitch together two very different corporate cultures after RCA acquired Whirlpool in the 1960s. The RCA group was changing planes in Pittsburgh on their way back from a Whirlpool meeting when one of the men looked at the others and asked, “Just what the hell is the matter with those guys?”

RCA, perhaps best known for its televisions, had sought to acquire companies that produced other home appliances – like washing machines – figuring it made sense to offer retail outlets a full range of appliances and electronics. As it turned out, Whirlpool’s vastly different ideas about pricing, distribution, and performance measurement eventually resulted in RCA re-selling the firm.

Over the past 20 years, as Silver has repeatedly coached companies through the same sort of growing pains, the business model has evolved from huge firms integrating every thinkable service to smaller businesses outsourcing all but their core concerns.

Looking forward, he says companies like Cisco Systems will continue to struggle if they don’t select the right companies to acquire and learn to digest them. “The same problems we saw with black, white, Jew, and gentile are now showing up on a geographic spectrum,” Silver says. “We’re still looking for a formula that works.”

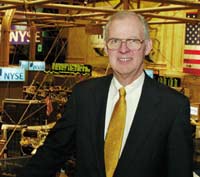

The Numbers Game

The old ticker tapes were not long gone when Thomas Haley, WG’62, started working at the New York Stock Exchange. The Dow had not yet cracked 1,500. On its busiest days, the exchange traded 50 million shares, the equivalent of a few minutes’ activity today.

But the most amazing thing is that it wasn’t that long ago. Haley was hired as the exchange’s controller in 1978, lured away by a headhunter from a job in finance administration at SAAB Scania. Since graduating from Wharton, he had worked for SAAB, Arthur Young, and several other accounting firms.

“There was a lot of automation going on behind the scenes,” when he arrived at the exchange, says Haley, 63. But the real change was still to come, and Haley would find he was a big part of it. Early in the 1980s, Haley “took off the green eyeshade” to become vice president for market data. At the time he started, he oversaw the distribution of updated price information to about 50,000 brokers and dealers via a network of terminals.

“There was a lot of automation going on behind the scenes,” when he arrived at the exchange, says Haley, 63. But the real change was still to come, and Haley would find he was a big part of it. Early in the 1980s, Haley “took off the green eyeshade” to become vice president for market data. At the time he started, he oversaw the distribution of updated price information to about 50,000 brokers and dealers via a network of terminals.

“In market data at that point, the objective was to get our information out to the broker-dealer community,” Haley says. Basically it was a professional-only audience.”

Today, he is responsible for seeing that 10 times as many professional investors receive data from the New York Stock Exchange. On top of that, the exchange sends numbers to millions of individuals via the Internet. Market data sales garner about $160 million a year, about 15 percent of the exchange’s total revenue.

The volume of information available has exploded, too. The exchange recently unveiled a new product called OpenBook, which lets brokers see the full range of bids and offers on a stock.

For Haley, it has been like sitting in the eye of the storm as he has watched the data he provides revolutionize investing. The ready availability of market data has created niches on Wall Street that couldn’t have been imagined 23 years ago, such as day trading and online brokers. It has changed investment banking, too, with innovations in derivatives and other complex investment vehicles whose values are pegged to market numbers. Financial information-based companies like Bloomberg have sprung up, using market data as their foundation.

Like so many other things, a pair of technologies made it all possible – personal computers and high-speed data communications networks. But even more important has been the exchange’s ability to use those innovations to provide a service customers want.

“The computer technology has been terrific, but really the issue has been customer demand,” Haley says. “What has been the success of the New York Stock Exchange is that the customer continues to use us.”

Family Ties

Even as the world’s premiere stock exchange pulled itself off the ticker-tape paper trail to become a processor-driven power-house, Stephen Co, WG’72, was fighting his own technology battle half way around the world.

Stock analysis, the intricacies of foreign exchange, and speculative markets captured his imagination at Wharton; and he went to work briefly for Marine Midland Bank, Singapore branch, upon graduation.

But his heart belonged in the family business: Steniel Manufacturing Company in the Philippines, a company named after Stephen and his brother Daniel. Stephen Co’s immediate family had fled to Singapore in 1971 as social unrest rocked the islands. Other relatives were left to tend the business, a fruit packaging concern.

By 1975, it was in the red, and Co headed home. Re-trenchment, perhaps, would have been the obvious choice. But Co – who calls himself a “born marketer” – had other ideas. “We just went in and took the competition head on,” he says.

Capacity was a problem. Steniel made carton boxes for materials from the U.S., and just-in-time delivery was a pipe dream. In the Philippines at the time, their suppliers were sometimes out of electricity for four to six hours a day. It took three to four months to import raw materials from abroad. Orders from the local mill took 60 to 75 days.

In 1976, the family ordered $10 million worth of state-of-the- art equipment, insisting supplier Mitsubishi cover any fluctuation in currency rates between order and delivery. They retired the accounting staff and computerized from top to bottom – payroll, inventory, the works.

Del Monte, Dole, and Chiquita were all buying; and despite three major economic crises in 15 years, the Cos had by 1990 turned the business around in a big way. Steniel went from a company with about a $5 million capital base to one with 10 times that amount, with no additional cash infusion from outside sources.

The Cos sold in 1990, and Stephen, who is now 52, went back to banking in Singapore. He had to relearn everything – starting with the way companies handled their IPOs. Soon after he moved into advising private clients, he was hired by Rabobank, a multinational financial services operation made up of about 370 local, independent banking cooperatives with roughly 800,000 members. Co became a senior vice president and head of its Philippine team.

So what does a guy with 15 years of experience running a family fruit packaging business have to offer as advice? He pulled those who would listen out of high tech before it tanked. He got them out of telecom stocks, too. And right now he says he’s “very, very convinced the market is going down to 8,000.”

Running a family business in the topsy-turvy Philippines in the 1970s, it would seem, was perfect training for private banking in the turbulent 2000s. For Stephen Co, running a family business in the Philippines in the 1970s was perfect training for private banking in the turbulent 2000s.

Foreign Exchange

Like Stephen Co, Nancy Boyer, WG’82, has worked in banking, advised high-ranking executives on their finances, and run her own successful business.

But that was all before she went to Wharton. Since graduating in 1982, her business experience includes a year at Cummins Engine in Columbus, IN.

But that was all before she went to Wharton. Since graduating in 1982, her business experience includes a year at Cummins Engine in Columbus, IN.

And that’s it.

“Once I was in the corporate world, I realized that making a profit is not my highest goal,” Boyer says.

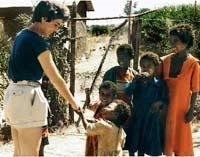

Less than a year after leaving Cummins in 1983, Boyer went to Ethiopia to teach English to seventh graders. Then she returned to the United States to embark on a career in foreign relations, a field where a Wharton education gives her a unique perspective. “Wharton gave me a lot of skills that have been very useful, and I’m very glad to have them,” Boyer says.

Knowing how to read a financial statement gives her a better understanding of major international developments such as the Argentine economic crisis. A more practical skill she developed at Wharton was “finding out how much can be done in a day,” Boyer says. “When I was a graduate teaching assistant, I used to go to a party until 11 o’clock and then grade papers ‘til dawn.”

She applauds Wharton’s efforts to extend those lessons, both abstract and concrete, to the rest of the world through its increasing international focus.

Today, Boyer is hoping to land a faculty position at the University of Delaware, where she earned a PhD from the department of political science and international affairs in 1999. She did her dissertation in Bulgaria, where she studied the effects of foreign aid on the country’s transition to democracy.

While Bulgarians are undoubtedly better off now than they were under communist rule, Boyer says, it was sad to see traditions abandoned in the quest for economic efficiency. Bulgaria has a delicious traditional yogurt, for example, that has been made the same way for centuries. It is so wholesome that Boyer’s son, who is allergic to dairy products, could enjoy it. But as Bulgaria embraces modern industrial food processing, the old stuff is getting harder and harder to find.

“I think that it’s really sad to see something like the very pure yogurt of Bulgaria be contaminated with the Land o’ Lakes technology,” Boyer says.

She often wonders what else the world is losing as globalization dissolves a hodgepodge of traditional cultures into an international melting pot. “There seemed to be more happiness and love in Ethiopia,” Boyer says, “than the isolation we have in the U.S. today.”

Risky Business

When Nancy Yaffa, WG’92, and two college friends opened a restaurant and cinema in New York’s trendy Tribeca neighborhood six years ago, they figured the movie theater would offer a hedge against the notoriously difficult New York restaurant business. But as they soon learned, Yaffa says, “the movie business is the second riskiest business you can get into.”

When Nancy Yaffa, WG’92, and two college friends opened a restaurant and cinema in New York’s trendy Tribeca neighborhood six years ago, they figured the movie theater would offer a hedge against the notoriously difficult New York restaurant business. But as they soon learned, Yaffa says, “the movie business is the second riskiest business you can get into.”

Film exhibition is very political, with theaters competing vigorously for the most promising new releases. The bigger, established theaters tend to win out in that competition, which put Yaffa and her partners, Henry Hershkowitz and Steven Kantor, at some disadvantage. Their 131-seat theater features mostly independent and repertory films.

The partners overcame that obstacle, and others, with sound management, creative marketing, and high quality. The dishes turned out by chef Mark Spangenthal are as inventive and sophisticated as you’d find in the New American temples of Union Square, according to the critics. “Better than it needs to be,” concludes the Zagat restaurant survey.

Yet as many a dismayed Manhattan restaurateur can tell you, “better than it needs to be” often isn’t good enough. Yaffa and her partners covered themselves by adding a second theater and an event room that has proven enormously successful. They started distributing a calendar to let customers know ahead of time what movies would be playing and created special events like a “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” brunch.

The dinner-and-a-movie concept really works, says Yaffa, 35. Customers can schedule their dinner reservations so they’ll finish dessert at show time. They can buy tickets from their waiter or waitress and get first dibs on seats when the theater doors open. No rushing to the theater, no lines, no need to communicate your urgent need for the check.

“It’s a convenience thing,” Yaffa says. “And when we have a good movie, the concept works incredibly well.” After a while though, she and her partners felt that chef Spangenthal’s great food was getting lost in the mix. “His caliber of food deserves its own place,” says Yaffa, whose regular haunts during her Wharton years were Carolina’s and Cavanaugh’s.

So she and her partners started The Living Room, a restaurant on the Upper East Side where the food is the main event. In many ways, Yaffa says, opening a second restaurant was more nerve-wracking than opening a first because she knew what she was in for.

Now Yaffa and one of her Screening Room partners, Henry Hershkowitz, have moved on to yet another venture. They’re collaborating with Madstone Films, an independent production, distribution, and exhibition company, to open theaters around the country. The first one, called the Madstone Centrum, recently opened in Cleveland.

Not every Madstone cinema will have a restaurant, but they will all have something – a cafe, bar, or lounge – that encourages patrons to linger. “The goal is really to create an experience where people see films and talk about films,” Yaffa says. “They’re definitely art cinemas.”

A Career in Jobs

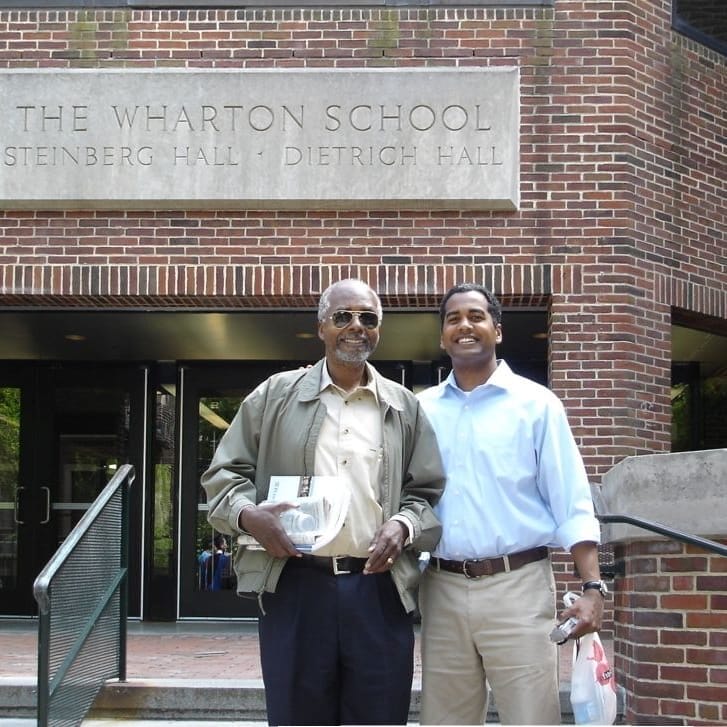

H.S. “Sam” Hamadeh, WG’97, didn’t need to find a job when he finished Wharton – he had a business to run. In May 1997, “basically the day after graduation,” Hamadeh started Vault, Inc. with his brother Samer and their friend Mark Oldman.

Their plan was to write and sell career guides to specific companies and industries, “sort of like a J.D. Power of the career world,” says Hamadeh, who has a JD from the University of Pennsylvania law school in addition to his MBA. Vault had a contract for eight books from publisher Houghton-Mifflin thanks to its partners’ previous experience as authors of career-related books. Even before he went to Wharton, and long before they dreamed up Vault, the company’s founders collaborated on “America’s Top 100 Internships” and a few other guides for young people trying to launch their careers.

Their plan was to write and sell career guides to specific companies and industries, “sort of like a J.D. Power of the career world,” says Hamadeh, who has a JD from the University of Pennsylvania law school in addition to his MBA. Vault had a contract for eight books from publisher Houghton-Mifflin thanks to its partners’ previous experience as authors of career-related books. Even before he went to Wharton, and long before they dreamed up Vault, the company’s founders collaborated on “America’s Top 100 Internships” and a few other guides for young people trying to launch their careers.

At first, Vault’s offices were located in the living room of Hamadeh’s apartment in New York City’s West Village. The company took orders by telephone and filled them right there, piling up the packages and mailing them at the end of the day. Their employees were college and high school students, many of them aspiring journalists who gathered and compiled valuable inside information about working conditions at America’s banks, law practices, corporations, and consulting firms. “It was very shoestring,” Hamadeh recalls.

Things went well. The company grew at a slow but steady pace, with infusions of cash from credit cards, family members, and a few angel investors. Then came the Internet. Hamadeh and his partners had heard of the Internet, of course. They created a website about three months after starting Vault, mostly to advertise their wares. But the idea that this medium would become their company’s main conduit to its customers was unimaginable. “I don’t think at the time we envisioned that this thing called the Internet would be such an important distribution mechanism,” the 30-year-old entrepreneur says.

Yet by fall 1998, Vault was taking 20 percent of its orders online. Then 30 percent, 40 percent, and pretty soon Hamadeh and his partners saw no reason to pay the cost of taking phone orders any longer. They also beefed up their website, adding job ads and bulletin boards where users could discuss the merits of various employers. Gradually, Vault became a dot-com. “We said, maybe we can go out and raise $10 million dollars,” Hamadeh says. “And we did.”

The venture capital allowed Vault to grow by leaps and bounds. It now publishes guides to more than 3,000 companies and 70 industries and offers human resources consulting to companies.

In August, Vault began offering its guides electronically, as encrypted portable document files. At the time, Hamadeh expected maybe 20 percent to 30 percent of the company’s sales would be made that way. “In reality, two-thirds order it online,” Hamadeh says. “Obviously, it’s the wave of the future for an information delivery company like ours.”

Vault remains first and foremost a publishing company, Hamadah says. Yet when he founded it five years ago, who could have imagined a publishing company that completes two-thirds of its transactions without printing, packaging, or shipping a single thing?

Matt Crenson and Sharon L. Crenson are national writers for the Associated Press.