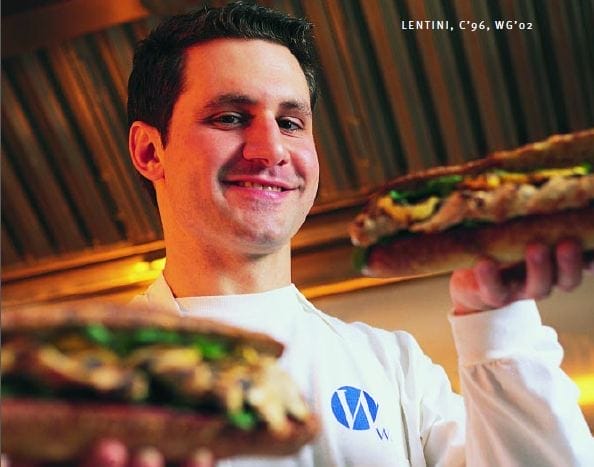

Marco Lentini, C’96, WG’02, wants to fix fast food. That’s fix as in repair, not fix as in prepare. With his freshly minted Wharton MBA and a gang of childhood chums, Lentini aims to found a fast-food empire that serves not burgers and fries but high-quality, healthy sandwiches made with all-natural ingredients. There’s a giant hole in the American restaurant business, Lentini says. People can find fresh, tasty, nutritious food at grocery stores like Whole Foods Market and Trader Joe’s. But when the discerning palate seeks lunch on the run, the world seems full of nothing but greasy patties and slimy shakes. Enter the Avanti Food Corp. “What we are is really a Whole Foods Market food philosophy adapted to a Starbucks operational model,” Lentini says.

The food business is a difficult one, but determined entrepreneurs can make millions by recognizing major consumer trends and capitalizing on them. Lentini is just one among a number of Wharton alumni who are satisfying the public’s endlessly evolving appetite for good food.

Make that alumni and students. Kun Hsu, W’03, hasn’t even graduated yet, but he has already launched a successful restaurant on Penn’s Sansom Row. The Bubble House serves various flavors of iced tea spiked with tapioca, a weird-sounding but incredibly popular and refreshing Asian drink.

Several other Wharton entrepreneurs are also responding to America’s growing openness to exotic cuisine. Assaf Tarnopolsky, WG’00, has brought a dollop of Paris to San Francisco in the form of West Coast Crepe King, a growing chain of take-out restaurants offering a meal stuffed in a pancake. Laurent Adamowicz, WG’84, is making a French connection too, by bringing Fauchon, the renowned Parisian luxury foods brand, to American connoisseurs.

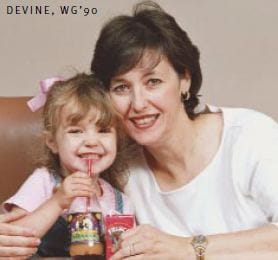

Denise Devine, WG’90, has latched onto another trend, the growing need for appealing children’s food that does not contribute to obesity. The rate of obesity among children has tripled in the last 20 years, threatening to spur an epidemic of diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses. Devine’s solution – a line of juices, frozen desserts, and other treats that give children the nutrients they need but not the empty calories they can do without.

Avanti Food Corp.

Marco Lentini, C’96, WG’02

Marco Lentini is betting on sandwiches, and he is not the only entrepreneur who believes in their potential. A whole herd of small chains such as Cosi, Briazz, Pret a Manger, and the Panera Bread Co. are vying for control of a business with annual sales growth of 15 percent.

Avanti was born in Wharton classrooms, where Lentini first developed a business plan for the venture and later worked out the details. He talked supply chains over coffee with Operations and Information Management Professor Marshall Fisher and grilled visiting CEOs from Borders Books and CompUSA on how they built their businesses. A marketing class helped him hash out the relative marketability of wraps versus panini (Italian grilled sandwiches on focaccia bread).

In the summer between his two years at Wharton, Lentini learned the coffee business in Central America, touring plantations and learning how to roast espresso in Guatemala.

When Lentini graduated in May, Wharton selected his business for its Venture Initiation Program, a business incubator that gives fledgling entrepreneurs free office space, computers, and telephone service. Now with bank investment and some of their own capital, Lentini and his partners are ready to fly.

The three founding partners of Avanti go way back, and their skills perfectly complement one another. Marco’s sister Jessica Lentini, the chief operating officer, has experience launching Starbucks locations in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Executive chef Anthony J. Marino, a childhood friend of Marco’s, has a degree from the Culinary Institute of America and experience in the kitchen at Le Bernadin, one of New York’s best restaurants.

In Avanti’s central commissary, an industrial kitchen in Runnemede, NJ, Marino will soon be preparing bread, spreads, dressings, and roast meats for branches all over the Philadelphia area – the first of which is scheduled to open on Penn’s campus early this summer. Eating in one of Avanti’s cafés (they don’t have a trademarked name yet) could be much like racing through Burger King for a quick bite. Customers in a hurry will be able to grab pre-made sandwiches, such as the house-made roast turkey with cheddar, cranberry chutney, and lettuce on a baguette.

But for those with time for a more relaxed experience, dining at an Avanti café can also be similar to lingering at Starbucks with a cup of java. There will be custom-made grilled panini – such as the Parma Prosciutto with mozzarella, a drizzling of basil, and roasted pine nuts – for those who can afford to wait a few minutes. And you can wash it down with freshly squeezed juice or a cup of gourmet coffee.

Like most food entrepreneurs, Lentini considers his venture more than just a business. He’s passionate about food, and he sees Avanti as a way to encourage the continued refinement of the American palate that has put high-grade Arabica coffee on every corner and brought sushi counters to suburban supermarkets.

“I definitely see peoples’ palates becoming more sophisticated,” he says. “What I want to do is take it to the next level.”

Bubble House

Kun Hsu, W’03, Greg Berman, W’02, Jeremiah Boorsma, W’02

In January 2001, Kun Hsu realized his home town had something that Philadelphia sorely lacked – bubble tea.

“In Toronto, it’s a big thing. It’s huge,” Hsu says. “Every couple blocks, you have a bubble tea shop.” Clearly, Hsu concluded, somebody had to do something. Bubble tea, an unusual iced beverage spiked with gummy tapioca balls that are sucked through an oversized straw, goes with college students better than frisbees and frat parties. They simply cannot resist its refreshing goofiness.

Invented in Taiwan about 20 years ago, bubble tea – sometimes called boba or tapioca tea – has become ubiquitous in Asia. In the United States, it is still limited mostly to Asian neighborhoods, college campuses, and California.

If you build it, Hsu thought, they will come. Whoever opened West Philadelphia’s first bubble tea emporium would reap unimaginable benefits. “Someone was going to do it,” Hsu says. “I thought that person should be me.”

That spring, he enrolled in Management 230, where he based his projects on the bubble tea business and shared the idea with a few classmates. By the end of the semester it was decided that three of them – Hsu, Greg Berman, W’02, and Jeremiah Boorsma, W’02 – would build themselves a bubble house.

Hsu learned of a vacant bakery on 34th and Sansom, right next to the legendary White Dog Cafe. When he and his partners approached landlord John Wicks with their business plan, he did more than say yes. He wanted in.

Undercapitalized and inexperienced, the partners labored mightily but still fell behind. They had planned to open their restaurant in four months. It took twice that long. “Nothing that we set out in our original business plan turned out to be true at all,” Hsu says. “We were totally unprepared.”

After the restaurant did open, Hsu, Berman and Boorsma were there ten hours a day washing dishes, taking orders, bussing tables, and fretting over the daily receipts. “We just never really thought that it would be so much work,” Hsu says.

Academics were all but obliterated by the pressures of starting and running a business. Hsu managed to get through the year with passing grades but admits it was probably a mistake to start a business while still in school. It wasn’t such a big mistake, though. The Bubble House has prospered. Now, Penn students stroll around campus sucking tapioca balls through oversized straws. In fact, Hsu credits his Wharton classes for some of the enterprise’s success. Though he probably could have learned through experience most of the skills he needed, “it would have taken me much more time on the spot to learn it as I go,” he says. “That time could have been the difference between success and failure.” The business broke even a year ago and expanded to include a full pan-Asian food menu in August. Food now accounts for 40 percent of total sales, with loose-leaf teas accounting for another 30 percent and bubble tea the rest. Having graduated, Berman and Boorsma are managing the business full time. But Hsu might be getting himself out of the bubble tea business. He’s talking to recruiters about a possible career in finance or consulting because the Bubble House just “isn’t as adventurous as it was before.”

Devine Foods

Denise Devine, WG’90

You’d think few things could be better for growing kids than fruit juice.

You’d be wrong. Though kids love it and parents view it as a natural, nutritious alternative to soda, fruit juice isn’t really such a wholesome thing for children to drink. Most fruit juices contain mainly water and sugar. They are high in calories but relatively low in nutritional value. Pediatricians cite fruit juice as one of the main culprits in America’s growing epidemic of childhood obesity.

“Although juice consumption has some benefits, it also has potential detrimental effects,” the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded in a 2001 policy statement. “Excessive juice consumption and the resultant increase in energy intake may contribute to the development of obesity.”

Having watched her own children guzzle fruit juice with abandon, Denise Devine is dedicating herself to improving children’s diets with a line of products that sneaks nutrition into foods that kids like to eat.

Her company, Devine Foods, has produced “Fruice” – a “drinkable snack” that tastes like juice but contains fiber and vitamins that juice doesn’t have. The fiber is especially important because it fills kids up, keeping them from consuming too many calories.

“The key is that it contains the whole food,” Devine says. Devine came to food entrepreneurship as a frustrated mother. Her son was a juice junkie, and there was little she could do to slake his thirst. “He drank a gallon of juice a day,” she says.

She looked for more nutritious juices but couldn’t find any. After doing research on children’s nutrition for years, she started working with the International Food Network at Cornell University, a laboratory that usually develops technology for major corporations.

Devine had just earned an MBA at Wharton, an experience she credits for teaching her to “think big.” She also had experience in the food business as manager of finance and investment strategy at Campbell Soup Co., the job she quit to pursue her dream.

It wasn’t easy to abandon a successful career for an uncertain new enterprise, but Devine says the dream just wouldn’t let her be.

“I got to the point that this was haunting me. This feeling was haunting me,” she says.

Inspired by Devine’s vision, the International Food Network’s scientists developed a way of turning vegetables and whole grains into a tasty, nutritious beverage. The same patented technology can be used to create shakes and a non-fat frozen dessert.

Devine now faces the daunting task of getting a major food company interested in making juice better for children. The industry has become more aware of nutritional issues in the last few years but still may not be ready to try something as different as Fruice.

“They realize that this isn’t going away, the issues surrounding obesity,” Devine says. “But as big companies, they move very slowly, and they don’t quite know what they want to do.”

And because the food industry is market driven, most companies want to see sales before they’ll take on a new product. Fruice is available in some health food stores and a few supermarkets in the mid-Atlantic region, but despite “talking with a lot of big companies,” Devine has not found one willing to distribute it widely.

“Hopefully, there will be some enlightened companies out there,” Devine says.

Meanwhile, she keeps innovating. Devine Foods has deals to serve its frozen dessert in cafeterias at Villanova and Temple and is working on one with Penn. Devine has also submitted a variation of the Fruice technology to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval as an over-the-counter drug.

The important thing is not making money but “having the products reach people so that they can be useful,” Devine says. “You have to constantly be focused on the end game.”

West Coast Crepe King

Assaf Tarnopolsky, WG’00

When life handed him lemons, Assaf Tarnopolsky made crepes.

Tarnopolsky was living the fast-paced, jet-set, dot-com life as director of international development for the Industry Standard, the trade magazine of the Internet boom. It was Buenos Aires one day, Bangkok the next.

And then one day, it was over. Facing bankruptcy, Tarnopolsky and a few colleagues made a last-ditch effort to rescue the magazine.

“We had to have a deal consummated by the day we went to bankruptcy court,” Tarnopolsky recalls. That day was Sept. 15, 2001. Four days after the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center, a defunct Internet business magazine had no takers.

Tarnopolsky endured a few “depressing” job interviews that fall. All they did, he says, was convince him that “the next great media job in my life was not going to be right around the corner.”

So he turned to crepes. He had actually been making and selling them for a few months at farmers’ markets in the San Francisco area, thanks to a bolt of inspiration that struck during a trip to Paris that summer.

In the French capital for a friend’s wedding, Tarnopolsky’s every meal came folded in a fluffy pancake. He simply could not get enough crepes. “I must have eaten five or six a day,” he says. “I started thinking, this doesn’t exist in the states, and they’re so good! Why doesn’t this exist in the states?”

When he got back to San Francisco, Tarnopolsky convinced his wife Nancy, WG’00, to let him buy an industrial crepe press for about $800. Before long, the two of them were peddling crepes on Saturdays and Sunday mornings.

“We were making our walking around money for the week and then some,” Tarnopolsky says.

They were also having a blast. So Tarnopolsky decided to devote himself to crepes. He found a weird little kiosk in a park on the edge of San Francisco’s financial district, an historic landmark from the 30s that had been saved as part of a skyscraper development deal.

Now the one-time new media titan was cracking 300 eggs at five every morning, and loving every minute of it.

“I feel like I’m in a position to really be successful. I own the majority of this company, and I think it’s a concept that has a lot of potential,” Tarnopolsky says.

Pretty soon it was time to expand. Thanks in part to the irresistible press appeal of a media titan turned crepe king (Tarnopolsky appeared on “Donahue,” National Public Radio, CNBC, and all the local news shows; he also made the pages of The New York Times and The San Francisco Chronicle), it wasn’t hard to find the financing he needed.

West Coast Crepe King now has two locations in San Francisco, and Tarnopolsky envisions up to four more in the next year.

“My long-term goal is to dominate the globe,” Tarnopolsky says. “But for the time being,” he adds, “the Bay Area and environs.”

Fauchon

Laurent Adamowicz, WG’84

It is not a good day for shopping. But inside Fauchon’s Park Avenue store, the frigid February gale that is raking Manhattan’s streets and avenues quickly dissolves into a sea of warmth and luxury.

Fatigued, frozen shoppers settle into soft chairs in the store’s tea salon for a restorative plate of petits fours and a cup of Darjeeling or Earl Grey.

In the retail store, Laurent Adamowicz is helping a customer who wants passion fruit preserves.

“In the world, you’re not going to find a line of preserves this rich,” says Laurent Adamowicz, sweeping his hand past shelves of exotic jams and jellies.

There are strawberry preserves with rose petals and preserves of bitter orange from Seville. There are peach preserves with Szechuan peppercorns.

This is not your neighborhood supermarket. Fauchon carries 43 kinds of mustard and 96 different spices. There are more than 100 varieties of tea. “We don’t want to be the everyday store with the everyday products that everybody has,” Adamowicz says. “We’re the symbol of French gastronomy.”

Adamowicz took over what is arguably France’s most beloved culinary institution in 1998, after 14 years in the food business. At the time, there were Fauchon stores all over Europe and much of Asia, but none in the United States. If American gourmets wanted traditional fruit confits or perfect croissants, they had to make the pilgrimage to Fauchon’s emporium in the Place de la Madeline.

Since buying the company, Adamowicz has opened two Fauchon locations in New York, one on Park Avenue and the other on Madison Avenue at 77th Street. A third store is about to open on Third Avenue.

In the rest of the United States, gourmet shoppers can find a selection of Fauchon products at Neiman Marcus stores. Adamowicz inked a deal with the department store in October.

The company was founded in 1886 when Auguste Fauchon began selling produce from a wooden cart. He soon gained a reputation for having the freshest and most exotic fruits and vegetables in Paris and by 1890 had a shop in the bustling Place de la Madeline, where he added wine, foie gras, coffee, and teas to the inventory.

In 1898, Fauchon opened the first Salon de The in Paris. Of all the gourmet foods the store sells, tea remains the most celebrated. Of the more than 100 varieties, there is a black tea flavored with cupuacu, an Amazonian fruit that tastes like pina colada, and Soir de France, a blend of China and Sri Lanka teas flavored with apricot and blood orange and sprinkled with orange peel and petals of rose and sunflower.

In 1905, Auguste Fauchon began selling his wares by catalogue, making them available to epicures all over Europe. The company continued to innovate throughout the 20th century, creating the first flavored teas in the 1960s and the first flower-petal teas in the 1970s. Now its 200 chefs concoct both traditional French delicacies and avant garde creations such as mustard flavored with smoked Lapsang Souchong tea.

When he enrolled at Wharton more than 20 years ago, Adamowicz says, the United States wasn’t ready for a store like Fauchon. He had decided to attend an American business school after France elected a socialist government in 1981 and chose Wharton for its international orientation.

After graduating, he worked for Beatrice Foods and a number of international companies before starting his own business in 1992.

America is a challenge for gourmet food purveyors, Adamowicz says, partly because the market has only recently developed for top-notch food products on this side of the Atlantic. Even more difficult, he says, are the regulations and trade barriers that keep all raw milk cheeses and many meats, pates, and similar products out.

But there is no obstacle to bringing genuine Parisian pastry to New York. Adamowicz has 23 pastry chefs on Long Island making petits fours, croissants, brioche, and other delights. The techniques and the ingredients come straight from France. In the case of the croissants: flour, fresh butter, fleur de sel from Gironde, and Volvic mineral water.

People who return from Paris often declare that the croissants they have just enjoyed cannot be had anywhere else in the world. But they can, Adamowicz believes, if you transport everything – the techniques, the talent, and the ingredients. Fauchon has all three.