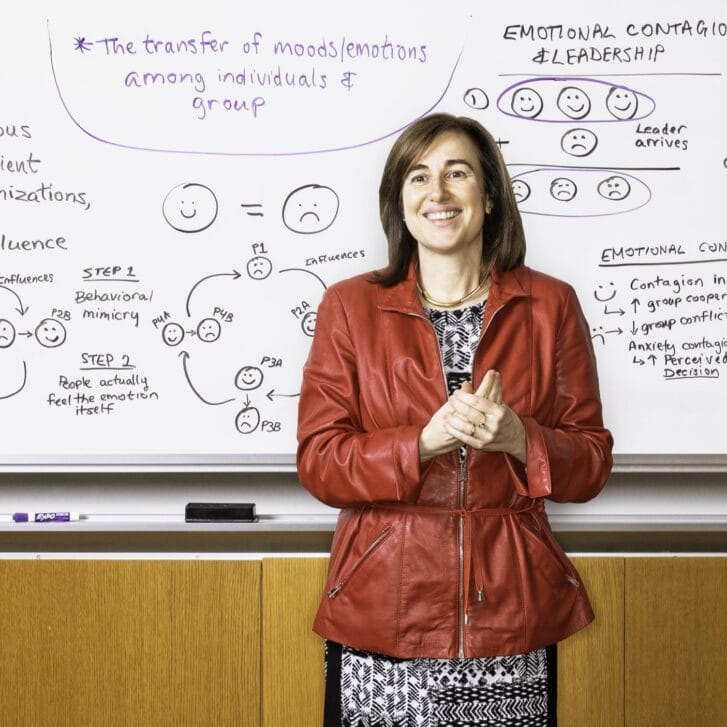

Years ago, shortly before Wharton Management Associate Professor Sigal Barsade went to graduate school, she worked in a group that included a curmudgeonly, crabby coworker. Since Barsade wasn’t working closely with “Crabby,” she assumed this woman had no effect on her life. That is, until Crabby went on vacation.

“The group became a much more sociable and pleasant place to be,” recalls Barsade, an associate professor of management. “Then, when she returned the next week, everybody got uptight again. I remember how striking it was. It wasn’t that she was telling us what to do, but just the way she was in the workplace that was influencing others.”

Barsade says that the experience led directly to her research into “emotional contagion,” the transfer of moods among people in a group. Emotional contagion and other emotional effects interest Barsade because they help explain phenomena that, on the surface, may not seem rational.

“There are things that go on that don’t seem to make sense,” Barsade says—things like the effect of somebody else’s mood or general disposition on your own productivity. “If they’re doing a technical task effectively, why would the fact that they’re curmudgeonly affect other people’s work? Or why, if on the way to work I got into a traffic jam and was cut off by a driver, would I then be more likely to reject projects in an innovation meeting four hours later? That’s not rational, but it happens.”

It happens for two reasons: people are emotional creatures and emotions are social. “No person is an emotional island,” Barsade likes to say. “We’re walking mood inductors,” passing our own moods on to others, who in turn pass them on to people they encounter.

Proving the Ripple Effect

Several years ago, Barsade found substantial evidence of this ripple effect in an experiment involving business students engaged in a group decision-making exercise. Barsade’s team videotaped and analyzed the interactions of four groups of students acting as managers trying to agree on how to divvy up a fixed sum of bonus money among their employees, with each manager arguing on behalf of his or her own candidate.

Unbeknownst to the participants, each group contained a confederate—a drama student named Rick who’d been specially trained to act out a different mood and energy level with each group. The result: even though his requests were the same with all the groups, the participants acted differently in direct response to Rick’s mood in their group. In the two groups where he exuded negativity, the other participants took on his bad mood—and behaved less cooperatively. And when he acted calm and happy, the rest of that group was pleasant and cooperative.

“I was in the room,” recalls Barsade, “and it was palpable: you could just see the emotions being transferred among the students.”

This result wasn’t unexpected: over a decade of research has shown evidence of social contagion, and some of the groundbreaking findings made it into Malcolm Gladwell’s bestseller The Tipping Point. But even Barsade was surprised by at least one result from her own study: positive emotions were as contagious as negative ones. In fact, in the two groups where Rick acted in low-energy ways, his good mood proved more contagious than his bad mood. That low-energy/positive group, apparently influenced by Rick’s demeanor, actually suggested giving him more money than he’d asked for. (And even months after the experiment, when fellow participants would pass Rick in a Wharton building where he was taking one class, they would treat him differently depending upon the mood he’d acted out in their group.) Barsade’s conclusion: positive and negative emotions are contagious, and the more positive the emotion the more cooperation and less conflict.

Part of what’s interesting about this experiment is that even though the participants were clearly influenced by Rick’s mood, none of them seemed aware of what had gone on. In fact, in a post-negotiation multiple-choice survey, everybody connected their personal effectiveness in the negotiation with other factors: nobody seemed to think that their decisions had anything to do with their mood or the mood of others in the room.

Subconscious Reactions Have Measurable Impact

Such obliviousness to the ways emotions affect our thoughts and actions is typical, Barsade says, as emotional decision-making often occurs on a subconscious level. In one study looking at how emotions influenced the hiring of customer service workers for an HMO, she and professor Lorna Doucet of the University of Illinois found that the strongest predictor of somebody’s being hired or passed over was not the resume or any other factor; it was the candidate’s susceptibility to emotional contagion. The greater a candidate’s propensity toward emotional contagion, the less likely he or she was to be rated highly and to be hired. And the interviewers didn’t seem to know that they were rating candidates according to that criterion. “Here’s an emotional tendency that people are picking up on that they’re not necessarily aware they’re picking up on,” Barsade says.

But it’s not just that people made subconscious, gut-level hiring decisions. In this case, the emotional decisions actually made a lot of sense. After all, it’s very reasonable that workers hired to answer calls from irate customers cannot be as effective if they’re overly swayed by the emotions of others. In fact, the ability to stay even-tempered in such circumstances might be more important to success in this job than any seemingly more rational, objective factor. As Barsade puts it, “It might seem irrational, but for the organization it ultimately makes sense.”

Many of the dynamics of social contagion are still a mystery. For example, if both positive and negative emotions are contagious, what determines which emotion prevails in a given group? Do managers and other leaders have much emotional influence on their followers—or are they, as some research suggests, actually more susceptible to emotional contagion than the typical group member? At least one thing is certain, Barsade says: “Whenever we interact with people, we’re constantly exchanging mood back and forth.” And as the negotiation study showed, even just one person can start an emotional wave that ripples throughout a group. Through enough influential individuals, an organization can develop an emotional culture that has rippled out through people feeling and conveying either positive or negative emotions.

Some organizations understand the power of emotions in the workplace and actively foster a positive emotional culture. Barsade says that Mary Kay Cosmetics encourages “positive programming.” Similarly, the professor cites a Southwest Airlines ad that suggests the employees’ positive spirit rubs off on customers.

That kind of culture may well attract a certain kind of personality. Barsade describes a videotape of Southwest’s former VP of Human Resources Elizabeth Sartain talking about what drew her to the airline. Her boss at her previous company had once chided her for laughing loudly in the hallway, saying it was unprofessional to be “cackling” in that way. Not so at Southwest, Sartain said, where she could laugh with abandon.

By calling her laughter unprofessional, the old boss was clearly expressing his company’s norm about emotional expression. (Barsade points out that, oddly enough, more companies are comfortable with expressions of anger than of joy, according to one study.) But the incident also illustrates another area of Barsade’s research: emotional diversity among coworkers.

A Little-Considered Aspect of Emotional Diversity

Barsade says that while there’s been a lot of research on demographic diversity in the workplace—the effect of differences such as ethnicity, gender, and age—few scholars have looked into differences in emotional styles. And that’s somewhat surprising, given that people often attribute problems at the office to personality clashes. In a study entitled “To Your Heart’s Content: A Model of Affective Diversity in Top Management Teams” published in Administrative Science Quarterly, Barsade and several colleagues used their remarkable access to psychological data from the uppermost echelons of corporate America to analyze some of the effects of emotional diversity. They found that a good emotional fit between a CEO and his or her top managers was strongly related to positive attitudes about the group and a sense of greater influence over group members. Not only that, there was a connection with the bottom line. Quite simply, “the more [emotionally] diverse the team, the less money the company made,” Barsade says.

She argues that this link is no coincidence. “Each of these people has a personality that makes other people think that others in the group are like them, and that leads to both better group processes and the ability to manage the company in a better way as exemplified by profits,” she explains.

Putting Organizations on the Couch

Barsade brings the topic of emotions into every class she teaches, from the Foundations of Leadership and Teams course for MBA students to her talks to executives. Lesson number one: dismiss the importance of emotions at your own peril. “If we don’t think about emotions, it’s to our detriment because they’re still influencing us. Emotions are productive sources of information and a means of communication that should be paid attention to and not viewed as superfluous or distracting noise,” she says.

Emotions can influence not only our attitudes, but also our decision making and even our behavior, as the emotional contagion study showed. But knowing something is happening gives us insights into what we’re doing and why—and can help keep us from becoming slaves to our emotions. For example, Barsade describes the all-too-common experience of coming into a meeting feeling annoyed and irritated and “finding ourselves screaming at somebody who’s not the person we’re mad at.” We’re less likely to let that happen—and risk damaging relationships—if we understand the power of emotions. Likewise, being aware of the possibility of emotional contagion helps us resist it.

Affective/Effective Strategies for the Workplace

By if emotions are so powerful, how can we resist catching them? One way is to avoid making a strong nonverbal connection with the other person. Barsade suggests not looking at the person too directly—or even leaving the room, if possible. If avoidance is impossible, you can try reasoning your way out of catching the bad mood. “Realize that this is happening, that you are not actually upset—that it is the other person who’s upset—and actively regulate your emotion,” Barsade advises. A further step is to bring the negative emotion into the open by labeling what’s happening out loud and even asking your colleague why she is feeling anxious or angry. Barsade acknowledges that it may seem difficult to bring up such emotions head-on, but nonetheless she says that the simple act of labeling emotions can often lead the other person to become self-aware—and thus better able to control her feelings. This is particularly true if it is a good relationship, she adds, “but can also work in not-such-good relationships, if people don’t want to be publicly perceived as being negative.”

Emotion and reason have classically been seen as opposing forces, and the insight that changing your thoughts can change your feelings forms the basis of a popular form of psychotherapy. But the true relationship between thoughts and feelings is far more complex. Not only can thoughts lead to feelings (good or bad), but feelings also lead to thoughts and actions, which can feed off each other. “Emotions and reason are completely intertwined,” Barsade says.

“I’m not saying that emotions are necessarily primary,” she adds. “What I’m trying to do is to get people to understand that emotions are an important piece of information that they can use to understand their world in general—and work in particular. Emotions matter.”

Marina Krakovsky is a San Francisco Bay-area journalist who writes frequently about business, psychology, and science.