A riddle: What does Brahms have to do with business? Mozart with marketing? Telemman with taxes?

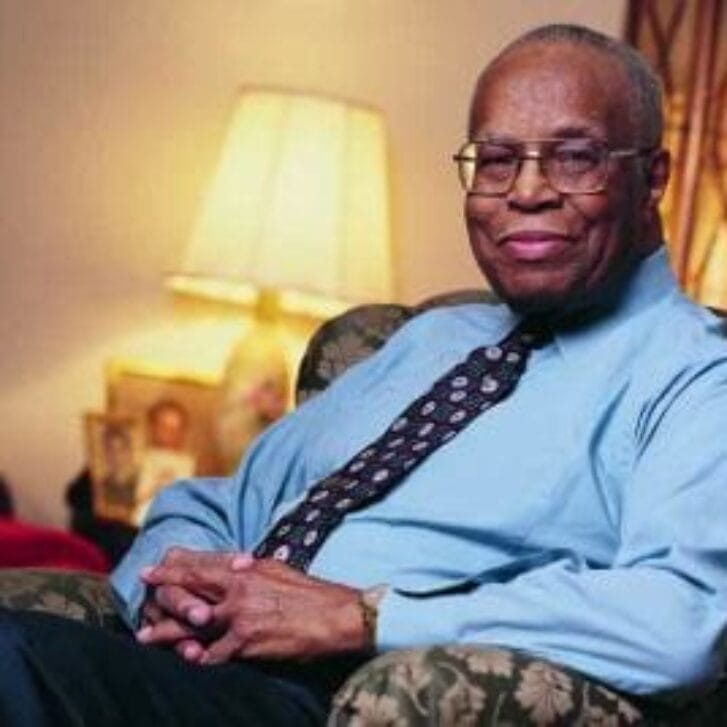

A single Wharton alumnus is the common key. His name is James DePreist, W’58, and he is seemingly one of a kind among the thousands of Wharton graduates worldwide.

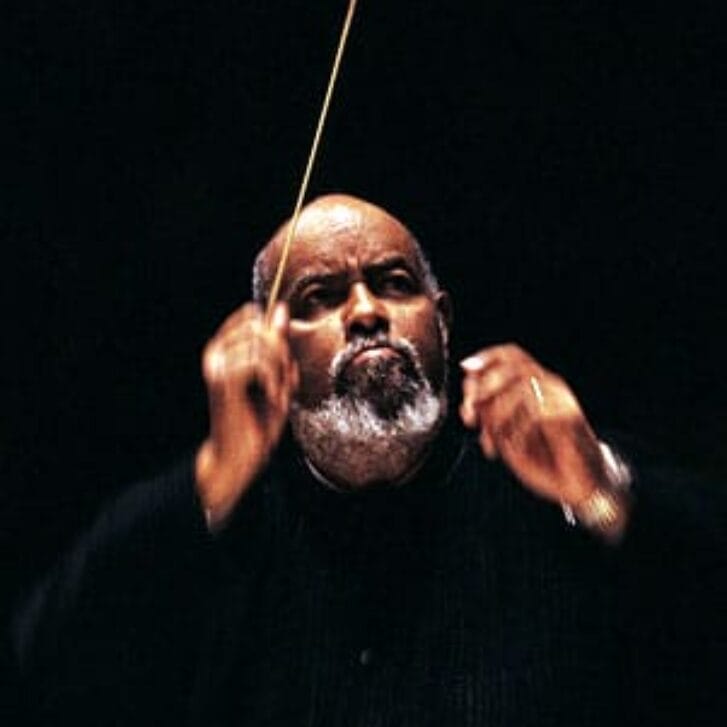

As many alumni do, DePreist travels the world. He’s among a smaller number who can command the rapt attention of international dignitaries. And he regularly finds himself the center of influence in cavernous halls filled with awestruck admirers.

DePreist is among the world’s small cadre of elite orchestral directors, and as one might imagine, he wields his Wharton degree in a manner very different from any other business graduate he has ever met.

“At the time that I was at Wharton it seemed very logical. I was going to be a lawyer,” DePreist recalls. “I was making a geographical separation in my mind between those things that brought me a great deal of pleasure, and practical things. All of my musical activities were both avocational and extracurricular.”

He played piano and had a jazz group. He studied musicology at Penn and composition at the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music. He even managed to squeeze in a second degree—a master’s from the Annenberg School in 1961. (He received an honorary degree from Penn in 1976 as well.)

But it was the following year that seems the turning point in DePreist’s professional life. The U.S. State Department invited him on a tour of Asia that included jamming with the King of Thailand’s personal band. The trip also led to a session conducting Bangkok’s symphony orchestra and from there, the young musician went on to win first prize in the Dimitri Mitropoulous International Conducting Competition. Soon, Leonard Bernstein himself selected DePreist as an assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic for the 1965-66 season.

Perhaps a musical career was preordained. DePreist is, after all, the nephew of renowned contralto Marion Anderson, the Philadelphia-born singer whose opera performances captivated audiences from her New York debut in 1924 through her farewell tour in 1965.

Like his aunt before him, DePreist is considered a magnetic performer. During a recent tribute by supporters of the Oregon Symphony, where DePreist made his orchestral home for 23 seasons, several people said the maestro was a prime attraction for both die-hard subscribers and those who visited the orchestra only during its free performances on the city’s riverbank.

“He’s Oregon’s cultural icon,” remarked one of DePreist’s admirers.

“I’d call him a multi-tasking demon,” former Oregon Gov. Neil Goldschmidt once said. “In addition to the music, he was involved in any number of things: fund-raising, promoting and transforming the orchestra.”

U.S. Sen. Mark Hatfield called DePreist the dominant figure in the state’s cultural life for twenty years, saying: “I know of no person with his longevity and impact, and not just in the arts. His style, dignity, confidence, humility are all unforgettable.”

Unforgettable primarily because of the transformation he basically willed upon the Oregon Symphony. When DePreist arrived in Portland in 1980, the orchestra was strictly part-time. Members did not have a dedicated rehearsal venue. They shared performance space at the city’s civic auditorium.

“First and foremost, he put this orchestra on the map artistically,” says Carrie Kikel, vice president of public relations for the symphony. DePreist led the campaign to convert what was then Portland’s Paramount Theater into what it is today: the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, a place dedicated to music and its primary tenant, the Oregon Symphony. Having a full-time home meant the ability to turn the group into a full-time orchestra complete with recording contracts, Kikel says.

Often hailed as one of America’s most respected conductors, the maestro has also directed every major North American orchestra, as well those of Berlin, Munich and Vienna, just to name a few. His debut with the London Symphony is set for this spring.

Soon, DePreist will begin the next illustrious chapter of an already illustrious career. In April, he’s set to become Permanent Conductor of the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra. It’s a title he adds to a long list. Already the Philadelphia native is Laureate Music Director of the Oregon Symphony, Principal Artistic Advisor of the Phoenix Symphony and Director of Conducting and Orchestral Studies at the Juilliard School in New York City.

DePreist collected these multi-national titles despite a cultural environment which is, at least on occasion, distinctly adverse to American conductors (mainly because of a lingering bias in the international arts scene about the ability of American conductors to handle the works of great European masters).

DePreist says his Wharton degree is one of the unique characteristics that have served him so well in this challenging environment. He recalls an accounting professor who preached to expect no gains and anticipate all losses. It’s a motto DePreist believes is a good dictum for life. It also helps when he’s dealing with bankers and other business professionals who generally make up the boards of directors of American orchestras. “I found it very, very helpful to be able to communicate with them on their level,” he says.

“I found my Wharton education to be important because the assumption is that the conductor and music director are primarily responsible for spending money. It is very useful to be able to show you can understand the business end and help to raise money.”

Kikel, the Oregon Symphony public relations VP, says all music directors today are expected to be active in fundraising, but “In Jimmy’s case, I can’t imagine an individual who would be more charismatic in building relationships and charming donors.”

He proved that prowess during the 2000-01 season when benefactor Gretchen Brooks donated $1 million for DePreist and the Oregon Symphony to record their work.

“I am very proud of this orchestra and what it has become under Jimmy’s leadership,” Brooks was quoted as saying at the time. “I wanted to honor them in a meaningful way.” The gift, timed to coincide with DePreist’s twentieth anniversary with the orchestra, gave him complete artistic freedom over record label, producer, repertoire and venue.

Although DePreist has spun a golden career from his business education and passion for music, he says he’s hard pressed to offer advice for today’s highly focused business student. He himself simply found the desire to make music overpowering. And he realizes that it takes very different talents to make it as an artist than it does to make it in business. However, he strongly encourages those who want to use their business skills to benefit cultural institutions.

“There are any number of talented people who have an interest in music either working in managing major talent or working in finance for the major artistic institutions,” he says. MBA-types with musical backgrounds can certainly find a welcoming place for their talents in the administrative offices of a symphony orchestra.

“When orchestras fall on hard times, very often it is because of poor management … There is a great, great need [for qualified people],” DePreist says. “But,” he adds, “it requires a sensitivity and understanding that it is not like making widgets.”