Any problem can be approached from multiple directions. When that problem is as complex as world dependence on a diminishing supply of fossil fuels and resulting environmental changes, multiple approaches are not only possible—they are necessary.

Some of Whartons alumni are stepping up with solutions to this pressing is sue. They’re developing alternative resources, funding new technologies, and promoting conservation with the aim of reducing dependence on electricity and petroleum.

Clean, high tech industries are emerging as one of this centurys strongest eco nomic drivers. More than $7.3 billion of venture capital was invested in North American “clean tech” companies between 1999 and 2005, including more than 1,085 investment rounds in 628 U.S. and Canadian companies, accord ing to Cleantech Venture Network LLC, which tracks investment dollars in com mercially viable alternative fuels and energy. And across the Atlantic, Londons Alternative Investment Market (AIM) has become a prime listing candidate for clean technology because it offers looser regulation than the U.S. market, espe cially in the wake of Sarbanes-Oxley.

Tucker Twitmyer, C 90, WG 96, managing partner with Philadelphia based EnerTech, says his firm is already reaping benefits from its investments in clean energy.

When you have a trillion-dollar-a-year market in the U.S. that seems to grow at an inexorable 2 percent to 3 percent a year, it just begs for innovation,” Twitmyer told Wired Magazine. Twitmyer was among a group of venture cap italists who participated in a panel discussion about clean technology at the Wharton Private Equity Conference held in January 2006.

And the approaches used by alumni are diverse, rang ing from the first high performance electric-powered sports car to fuel cell development. Individually, they are venture capitalists, managers, technologists, and entrepreneurs, all moving forward on their unique ventures; taken together they are dynamic pieces of a complicated solution.

A Challenge in the Classroom

For Tom Arnold, WG’05, the connection from his Wharton education to his career in alternative ener gy couldnt have been more direct.

Arnold was one of 40 students who were challenged by Professor Karl Ulrich in his “Problem Solving, Design, and System Improvement” course in Fall 2004 to launch a viable business that would create a way for everyday drivers to compensate for the environmental damage they cause every time they turn on their ignition. Their deadline? Six weeks. Their budget? $5,000.

Within the timeframe, the students developed a business called TerraPass.

Here’s how it works: Consumers go to the TerraPass website (www.terrapass.com) and use a calculator there to measure how much CO©÷ their vehicles dump into the environment each year. The calculator accounts for vehicle make, model and year, as well as how much it is driven. Airline trips, can also be calculated.

Once a consumer has measured their carbon footprint, they can buy a TerraPass, which is used to fund the same amount of renewable energy projects as they are currently responsible for polluting. TerraPass is leveraging one renewable natural resource consumer guilt to finance others.

The projects result in verified reductions in greenhouse gas pollution. And these reductions counterbalance your own emissions, explains Arnold. An average driver emits 10,000 pounds in carbon dioxide in an average year. A TerraPass to offset those emissions costs between $39.95 and $49.95 per year.

In its first year, TerraPass grew to four full time employees and raised $500,000 in startup capital. The company has signed up 16,500 members and taken the equivalent of almost 6,000 cars off the road by funding nine clean energy projects.

It’s a great start, said Arnold, but he has some big goals: “I want to see a million members.”

The Greening of Detroit

Ann Manning, WG 87, manager of Sustainable Business Strategies at Ford Motor Company, worked with Arnold and TerraPass to create a unique partnership dubbed Greener Miles. This program allows Ford owners to go on line (www.terrapass.com/ford) and estimate their annual emissions from driving, and then offset them by purchasing a TerraPass that in turn will fund emission reducing projects.

Ann Manning, WG 87, manager of Sustainable Business Strategies at Ford Motor Company, worked with Arnold and TerraPass to create a unique partnership dubbed Greener Miles. This program allows Ford owners to go on line (www.terrapass.com/ford) and estimate their annual emissions from driving, and then offset them by purchasing a TerraPass that in turn will fund emission reducing projects.

Manning has also set up similar offset programs for some of their factories.

She said she keeps her focus simple: Hybrid cars. Alternative fuels. Efficient engines. They re all crucial steps in addressing climate change and global warming. Manning said there s another important step as well: better driving.

Think about it, she said. Can you make a bigger impact with a few thousand hybrid vehicles, or with a 1 mpg gain on millions of vehicles sold each year around the world?

This is exactly what Manning is thinking about. Her position at Ford is to innovate, market, create, and promote new strategies and initiatives that will keep the company driving toward the future.

Nearly seven years ago, Ford launched an initiative to address issues of climate change and human rights, recog nizing these items are an important piece of their business

Ford’s vehicles are already 99 percent more efficient than they were in the 1970s, said Manning, so the potential for squeezing even more miles per gallon for every vehicle is not nearly as great as it used to be.

Ford’s focus now is on carbon emissions, she said, targeting climate change and global warming at the tailpipe.

“You hear a lot about exciting new fuels that can do a lot about greenhouse gases,” she said.

Ford currently offers three hybrid vehicles in its lineup with two more on the drawing board, and offers four “Flexible Fuel” vehicles that can run on E85 ethanol. In addition, Ford’s manufacturing plants are pushing to be more green.

Manning’s job also includes convincing Ford’s customers and existing owners that the potential to reduce emissions is a lot greater than just the new technologies.

“We want our customers to think, “How can I be part of the solution?’” said Manning. “We figure, let’s work on all the new technologies coming around the bend, explore the potential not only for climate impact and market reception, but at the same time, right now, let’s focus on helping drivers understand what they can do. One thing is Eco-Driving.”

Here’s what Eco-Driving is: gentle accelerating, staying at the speed limit, constant speeds, smooth decelerations and turning off a vehicle rather than letting it idle for long periods of time.

And Manning has an even simpler solution: drive less.

“It’s all about creative thinking,” she said. “We learned at Wharton to take different approaches to the same problem. At Ford, our focus isn’t just on what different things we can do to our vehicles, although no doubt about it our biggest focus is on that. But there are other ways, and I’m able to look at those as well.”

High Performance, Cleaner Technology

While hybrid cars like those from Ford-powered with electricity and petroleum—are working their way onto U.S. freeways, Elon Musk, W’97, hopes to take low-emission cars to a whole new level with Tesla, a high-performance, highly efficient electric sports car that doesn’t burn any oil at all.

“I guess electric cars always seemed to me to be the obvious mode of transportation for the future,” said Musk. “Fifty years from now people will look upon gasoline-powered cars the way we look at steam-powered vehicles today: outdated and outmoded.”

Tesla is one of several eco-business ventures Musk is involved in, and he is extremely optimistic about the entire genre.

Take this comment: “The solar industry is going to be gigantic, way bigger than the Internet,” he said.

Coming from Musk you’d be foolish to do anything but take this prediction seriously. Musk has launched and sold a series of successful businesses including PayPal, which was acquired by eBay for $1.5 billion in stock in 2002. So what’s he doing now?

Musk spends most of his time and energy working at SpaceX, a company developing and launching the world’s most advanced rockets for satellite and later human transportation. But he is also chairman and the lead investor in two cutting-edge alternative energy companies: Tesla Motors and Solar City, which aims to “bring solar power to everyone.”

Tesla Motor’s first production model is slated to roll out in December 2007, and Musk plans to own and drive the very first one. The first model, the Tesla Roadster sports car, is capable of going from zero to 60 mph in around four seconds, has a top speed of better than 130 mph, and can travel up to 250 miles on a single charge, which at today’s energy prices would cost about $3. It beats a tank of gas. The car’s power comes from its Lithium-ion Energy Storage System, or battery pack, which can be recharged in about 3.5 hours.

Musk’s second clean energy venture, Solar City, has the bold yet simple goal of becoming “the Dell computer of the solar space,” said Musk. “You have a lot of companies working on the photovoltaic cell itself, but not a lot of people are working on delivering the solar power solution to the customers.”

To achieve this, Solar City conducts assessments of homes or businesses that are considering going solar. The company will then install power systems that produce electricity during the day. Any excess electricity is sold back to the utility grid at retail process. Solar City is also acquiring existing small solar energy suppliers around the U.S. which are already providing power to some businesses and homes.

Musk said there’s a public misconception that converting to solar energy takes 20 or 30 years to pay off.

“People don’t yet realize that the return you get by installing solar panels on your roof today goes from a low of 10 percent annual return to a high of a 15 percent annual return. It’s actually already a very smart economical decision for a large number of households today,” he said. “I don’t know too many places where you can guarantee that kind of pay off.”

Musk said his company is not lobbying for government subsidies like those that existed in the 1970s and early 1980s.

“We think we have to make solar cost efficient enough that government subsidies are not necessary,” he said.

Bringing the price of solar down involves a lot of “fairly mundane” work, said Musk—process improvement, technology installations, monitoring panels, better assembly systems, better combinations of technology.

And although the largest solar energy users are outside the United States, Musk said Solar City’s focus so far is entirely domestic.

“The U.S. market is the biggest in the world, and I think that if the U.S. uses 25 percent of the world’s energy, that’s a big market,” he said.

A Solar Future

While Musk is launching new solar businesses, Bill Rever, WG’82, is working with one of the stalwarts in the industry as strategic marketing manager for BP Solar.

Rever first became interested in solar energy as a graduate student at Penn State, where he earned a dual degree—a master’s degree in engineering along with his Wharton MBA. It was an engineering course in solar energy, combined with the stimulating business classes, that led to his life’s calling.

Upon graduation, Rever said he “knocked on doors” of the top solar energy businesses, and was offered a position with a small but up-and-coming solar energy firm, Solarex. During the next 20 years, Rever came along as Solarex was purchased by Amoco, and again when Amoco was acquired by BP, one of the world’s leading energy companies.

BP Solar designs, builds, and installs solar electric systems for residential and industrial customers. The company has installed systems in more than 160 countries and has manufacturing centers in Australia, India, Spain, and the U.S.

The solar industry, these days, is almost entirely focused on solar photovoltaics, although there is still a small market for solar thermal products in India and other places. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the solar energy market in the United States was driven a lot by government demonstration projects funded by the Department of Energy. Photovoltaics were entering markets where it was economically justified, typically remote areas without conventional and inexpensive utilities. The market here flattened in the late 1980s, but started growing again in the early 1990s. Climate change and global warming, as well as reduction in access to petroleum, have brought new attention—and funding—to solar, said Rever.

Rever’s work has always been demanding, and these days travel is a constant, he said. In the 1980s, most of BP Solar’s markets were in less developed countries. Now the markets are mainly in the avant-garde of new energy and environmentally driven markets like Germany and Japan.

In the last year, with a leading role in the development of a global marketing strategy for BP Solar, Rever has visited Japan, Australia, China, Germany, and Thailand, working with officials to develop new markets. He said he hopes sometime to shift that focus domestically. The United States accounts for just 7 percent of the global market for photovoltaics, even though it consumes 25 to 30 percent of the world’s energy.

Rever said solar power is such a fringe player in the United States that many people assume that because he’s at BP, he’s in the petroleum business.

“If you’re a stock market analyst, you’re looking at BP as an oil and gas firm,” said Rever. “But we’ve been in the solar industry for 30 years.”

Greener Buildings, Greener Earth

Home solar systems are still too costly for widespread adoption, but Rever looks forward to that changing. There’s been a long history of cost reductions, he said, on average about 5 percent per year. Rever said the key factor keeping solar from becoming a financially viable alternative for homeowners are the historically low prices for other forms of energy. As electricity and gas prices rise, however, he said solar is becoming a more reasonable alternative, both economically and environmentally.

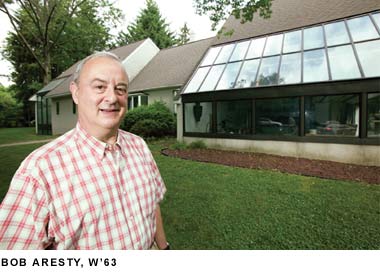

While Rever is working to capture and convert sunshine into power, Bob Aresty, W’63, is hoping to reflect and absorb those same rays.

Aresty is president and CEO of The Solar Energy Corporation (Solec), the world’s largest manufacturer of specialized, heat reflecting and absorbing coatings for solar, building, roofing, and manufacturing. The technology behind these coatings was developed in 1974 in a laboratory on a farm in Princeton, NJ, and today Aresty produces two types of coatings that insulate and control heat and light absortion and radiation. The factory itself, heated 100 percent by solar, has a glass front to make best use of passive solar heat.

The technology may look like just another layer of paint, but the chemistry of that coating can produce energy savings immediately. It sounds entirely too simple ? you paint on the products and your bills go down. Solec’s coatings can lessen air conditioning costs by 10 percent to 15 percent.

These days, as global warming make it more crucial than ever to reduce dependence on electricity, Aresty said the potential of his products is “really quite mindboggling.”

“I think of what we do in our little niche, we could do between $50 and $100 million a year, and we don’t do anything like that,” he said.

That could change. Aresty’s products are part of the green buildings movement, the larger trend to develop high-performance buildings that meet five areas of human and environmental health: sustainable site development, water savings, energy efficiency, materials selection, and indoor environmental quality.

The movement was marginal when Aresty began, but it is now mainstream. The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), has a membership of more than 6,900 organizations. McGraw-Hill Construction estimates that more than $59 billion will be spent annually on green building by 2010, up from $10.2 billion in 2004.

The imperative for greener building technology is worldwide. In November 2006, the Wharton Infosys Business Transformation Awards honored environmental entrepreneur Enrique Gomez Junco B. for leading Mexico toward greener construction. When Celsol, the company he founded to provide solar energy to hotels in Mexico, faltered due to lack of financing, Gomez Junco re-launched his business in 2000. Under the name Optima Energia the company has been building energy and water efficient buildings through performance contracting, saving its clients, 84 million kilowatts of electricity, 11.9 million liters of natural gas, 2 million cubic meters of water, 14 million liters of diesel, for a total of $1,000,000 (USD) a month.

Short and Long Term Solutions

Like greener buildings, biodiesel is a technology that is available now—it’s already a fuel additive for gasoline, and almost any engine that uses diesel can be converted to biodiesel.

In 2005, Tian Long, WG’00, saw the potential, and left investment banking to found one of Asia’s first biodiesel businesses: Vance Biodiesel. With corporate headquarters in Singapore and its production based in Malaysia, Long’s company is using local palm oil to produce a high-quality biodiesel that is helping supply Asia’s growing power needs while reducing carbon emissions.

Because the outlays of capital for biodiesel production facilities are massive, established companies are leading the way in the U.S. For example, DuPont is currently partnering with BP to commercialize biobutanol, an alternative to ethanol developed under the leadership of John Ranieri, AMP’02. While biobutanol is a superior product, producing it economically is the challenge.

“If you come in with an offering that is more expensive than petroleum and say, hey it’s green, consumers aren’t ready to pay for it,” said Ranieri at a Wharton Impact Conference in October 2006. “You have to find the places you go first ? the projects to do first. We have to find both quality and sustainability.” As a consequence, DuPont is introducing a range of sustainable products ? some, like seed corn that produces a higher output of ethanol, are available now, while others, like biobutanol, have longer-range commercialization cycles. (For more on how Ranieri manages innovative projects for DuPont, see p. 16)

In the Philippines, Vincent S. Perez, WG’83, similarly took a multi-pronged approach while serving four years as Energy Secretary until 2005, moving his country toward conservation and oil exploration, while pursuing greater reliance on clean, indigenous and sustainable energy sources including biodiesel and geothermal power. Solving the energy crisis requires immediate changes and long-term transformation.

Scott Schecter, WG’86, CFO of HydroGen Corp., is taking the long-term view to clean energy: the fuel cell. While commercialization is still in the future, success could be earth-changing.

Here’s how fuel cells work: a simple chemical reaction turns hydrogen and oxygen into water and electricity. Unlike a normal generator that emits pollutants, the only byproduct of a fuel cell is the pure water vapor. And unlike a battery, a fuel cell will continuously produce electricity as long as hydrogen and oxygen are supplied to it.

Schecter’s firm focuses on a type of fuel cell that uses liquid phosphoric acid as the electrolyte to conduct the electricity.

His challenges include expensive materials and limits to efficiency. His goal is cheap, reliable power.

“When we prove that we can do what we think we can do, this can truly be a game changer,” he said, “because we can produce power on a competitive basis with traditional fossil fuel powered generators, and at the same time have environmental benefits and a byproduct of pure water.”

HydroGen Corp.’s technology was developed by Westinghouse Corp. and the U.S. Department of Energy in a $150 million partnership in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 2001 a group of investors got together and took over the project, launching HydroGen Corp.

HydroGen Corp. acquired all of the intellectual property and hard assets developed in that program through a series of transactions. Now the company plans to install and operate its first major demonstration project, a 400 kilowatt fuel cell power plant, at ASHTA Chemicals Inc. chlor-alkali manufacturing plant in Ashtabula, OH. Installation is scheduled for 2007. The project is supported by a $1.25 million award from Ohio.

Schecter said that in their first five years, HydroGen has raised $40 million, and gone from an eight-person startup to a fast growing company with 60 employees.

Schecter came to HydroGen Corp. from another environmentally friendly fuel industry firm, where his focus was on air pollution control and fuel treatment technology.

“For the better part of 15 years I’ve been around green companies, trying to do something positive for the environment,” he said. Schecter said fuel cells are a source of power not reliant in any way on foreign governments. In addition, they produce pure water, an asset in arid climates.

The early high costs of the technology stalled its development. But these days rising power prices, as well as increased environmental regulations, are prompting renewed interest in alternative energies, he said.

“But no matter how green we are, or how wonderful we are, no one is going to buy our power if they have to spend more money,” he said. “Our business plan shows we can get the cost down to a level that will be attractive to industrial companies, particularly those that produce hydrogen as a waste gas.”

Capital Markets Are Open for Business

Elon Musk shares Schecter’s optimism from the other side of the investor relationship. He said that although his goal in investing in both Solar City and Tesla is to find solutions to climate problems, that aim will almost certainly reap a profit as well.

His hope is supported by recent events. In the past two years, several solar companies made huge IPOs. In 2005 SunPower, a unit of Cypress Semiconductor, raised $139 million in an offering underwritten by Credit Suisse Group and Lehman Brothers. Chinese solar company Suntech Power Holdings raised $400 million, and in Germany, QCells raised $288.5 million.

No wonder that clean technology has strong investment support via VCs, private equity, and traditional investment banks with an eye on the future.

According to the 2006 Cleantech Venture Capital Report on North American venture capital investing, by 2009, 10 percent of all VC investment activity will be in the arena of clean technology ? up from 3 percent from 1999-2001. That amounts to between $6.2 billion to $8.8 billion invested as venture capital firms go to the markets to raise capital in an estimated 1,000 rounds between 2006 and 2009. The energy component is the fastest growing sector, comprising upwards of 70 percent of investments in the industry, according to EnerTech’s Tucker Twitmyer.

And those sums don’t include the internal investments that public companies like BP and DuPont are pouring into clean technology.

At November’s Impact Conference, Ranieri shared the investment philosophy he follows at DuPont, a 200-year-old company that is transforming itself for a sustainable future. “Our commitment is to create shareholder value and societal value at the same time,” he said. “There is an upside to creating shareholder value in an environmentally sustainable fashion. Being green isn’t good just for itself ? it’s a proxy for good management.”

And if the projects funded take off, the whole world will benefit, not just the investors.

Musk concurs. “I think most of the things that do good in the world are also things that make money,” he said. “It’s unusual where you have a situation where doing good is incompatible with building a valuable enterprise.”

Martha Mendoza is a working journalist and a Pulitzer Prize winner. This article includes reporting from Knowledge@ Wharton, “The End of Oil? Venture Capital Firms Raise the Profile of Alternative Energy,” published April 26, 2006.