By Matthew Brodsky

Technology and growth have been synonymous for decades now. But unlike computing power, which theoretically doubles every two years according to a pop-culture translation of Moore’s law, expectations for a tech career have always been nothing short of fantastical. Steady growth, consistent buildup of opportunities and wealth like you might expect in bond trading were never enough. No, tech has always possessed the allure of astronomical professional and personal growth. The likes of Hollywood celebrity for founders and inventors, the share-option lottery for early employees. All for the chance to change the world in a visceral, systemic way.

Even when the Internet was simply something that connected libraries around the world, Marcos Galperin W94 could see that it was “something that was going to change the world and civilization.” In the 1990s when Galperin devoted himself to the life of a civilization changer, such sentiments could be considered California dreaming, particularly for an analytical bunch like Whartonites, but no one can argue that the world in which we live is not tech-enabled, tech-powered and tech-dependent.

The allure of a tech career is stronger than ever, particularly for more and more Wharton students and young grads. According to data from Wharton MBA Career Management, 11.3 percent of accepted positions for the Class of 2015 were in technology industries, up from 5.6 percent for 2010 (and compared with 36.9 percent for financial services in 2015). Geographic trends hint at an MBA career change as well—with 9.6 percent of accepted jobs in 2015 being in San Francisco, up from 4.3 percent in 2010.

Of Wharton undergrads in the Class of 2015, 10.1 percent went into technology (compared with 35.3 percent in investment banking). For the Class of 2010, that number was 4.4 percent.

Mandy Ginsberg, CEO of Match Group North America

With this trend in mind, we sought to explore what it takes to succeed in a technology career. We spoke with prominent alumni in the tech space to glean lessons from their own experiences, as well as to ask them point-blank for advice. And we spoke with younger alumni and current students to get a sense for why they’re attracted to the space.

We can hardly expect to explore such massive topics as “technology” and “careers” in one article—and we will continue to do so in subsequent issues, in different ways—but let’s start by exploring what it takes to be a tech success.

1. Company Fit

The approach that Rich Riley W96 employed to get into tech is the kind of story that thousands of American moms and dads nagged their sons and daughters with in the ’90s … and today. Why can’t you start your own business and sell it for millions to Yahoo!?

Riley mowed every lawn in his Austin, Texas, neighborhood growing up, and dual-majored in undergrad in finance and entrepreneurship at Wharton. But coming out of the School, Wall Street represented a great way for him to get exposed quickly to a lot of different industries and financial transactions and work firsthand with corporate leaders. His entrepreneurial spirit took over again, though, on a business-trip plane ride, when he had enough of typing in passwords for each and every Internet account. He and a friend conceived of a way to maintain people’s multiple online passwords in one spot. It eventually became the first browser toolbar. By age 25, in January 1999, after a bidding war among the biggest Internet companies of the day, Riley was negotiating its sale with Jerry Yang, Yahoo’s legendary founder.

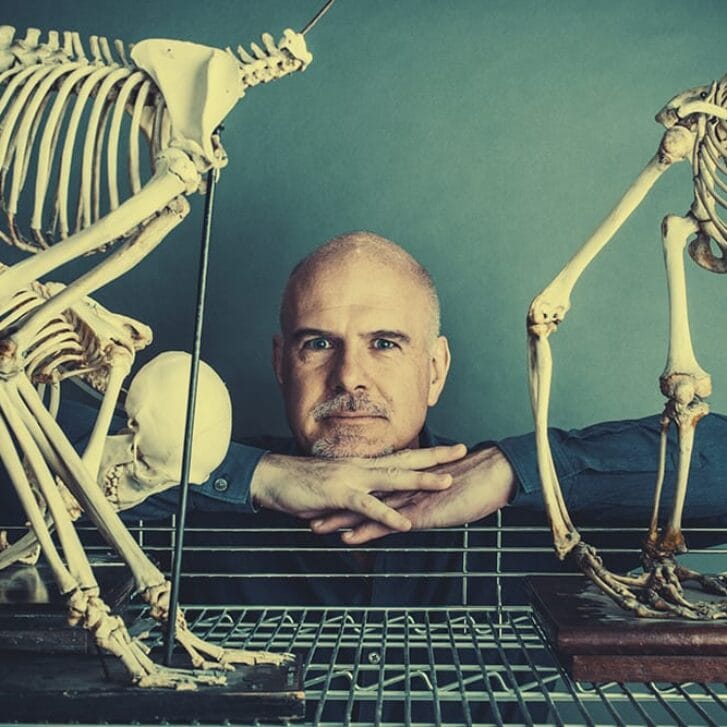

Rich Riley, CEO of Shazam

“It was a pretty surreal experience to be negotiating for a very material amount of money at the time with such a famous and impressive person,” Riley recalls, adding that the Yahoo offices back then had a “magical quality.” Hired as part of the deal to work on mergers and acquisitions, Riley was hooked not just because of the pioneering open offices. Yahoo was the kind of company where every 18 months he had a new, larger responsibility—the M&A role led to a $100 million deal, then operational roles and running a $1 billion business within Yahoo, followed by duties abroad overseeing all of Europe and the Middle East, culminating with his return to run the Americas and serve on the executive team.

Some industries, like finance, have incentive structures that reward individual achievement and foster competition among peers and internal groups. With technology, community and unity of purpose appear to be the higher calling. It helps explain why Riley was so successful at Yahoo.

“One thing I really always felt like an equity owner at Yahoo, and I always put the interests of the company first,” Riley says, whether he was negotiating a deal or cutting costs. “A lot of people get that backwards, and it hurts them.”

In essence, Riley lucked into a company that was a perfect match for him. His enviable role continues, as he now serves as CEO of Shazam, the pioneering mobile app company best known for being able to name a song by simply listening to it.

Today, however, it appears most tech recruits must be very particular about which company they want to work for. It’s not good enough to want to be in tech because it’s cool, or want to work in consumer tech for the bragging rights. Success in job interviews, then in subsequent positions, comes by knowing a company’s culture, its mission, its products (and preferably an employee or two) and being able to explain why you fit.

Before would-be tech professionals get to that granular level, at least narrow down whether you’re a better fit for enterprise or consumer tech, advises Anthony Noto WG99. If you have interest in the nuts and bolts behind the scenes, the enterprise tech route could be the better fit, he says.

(In case you’re interested, the company fit at Twitter, at least if you want to work with Chief Financial Officer Noto, is to be “committed to running after problems and willing to make your footprint bigger than your foot.”)

Part of this “fitting in” involves ensuring that your particular role is valued at a given organization. Nicole Anasenes WG02 has been in financial roles primarily during her two decades’ career in tech—in numerous roles at IBM that led to a divisional CFO role and then as CFO for enterprise software firm Infor—and she always knew that finance was viewed as an important partner with operations. But whatever your role, if it be non-technical—whether it be finance, marketing, HR, etc.—success will come if that company culture values it.

“Any time you commit your own personal time at a company you want to know you can create value there,” she says. “You want to ride a wave of being appreciated, rather than be required.”

Identifying your good company match, getting your foot in the door and scoring a position—or simply getting acquired into a great path such as Riley did—none of it matters, however, if you don’t perform once inside. It’s like getting into Wharton; you got into the top business school, and now you have to work your tail off to train and deserve your next great opportunity (this isn’t Harvard!). Marc Shedroff WG02 is the first to admit he lucked out by being there to “board a rocket ship” at YouTube after the Google acquisition, but he adds that you can’t always predict how or why opportunity will present itself. What you can control is working hard and taking on roles and responsibilities that are “accretive and helpful to your career going forward.” For instance, his role at YouTube was specific—licensing content from big producers—and he felt ownership over it and his team. He then was able to point to very clear accomplishments and continue onward and upward. He now serves as chief operating officer of Samsung Electronics Global Innovation Center.

2. Partner With the Right People

Along the way, of course, it helps to know the right people. Any Wharton undergrad who has friends in the Engineering School knows the power of one form of collaboration, a merging of strengths among equals.

“I don’t know how to write software but I spend a lot of time with people who do,” says Shazam’s Riley, whose teaching assistant at Wharton was Elon Musk C97 W97 (not particularly relevant to his career, but cool to note). “Finding ways to partner with brilliant technical minds … is the magic combination.”

“The key, aside from just hiring very good engineers—product talent, development talent, etc.—is also making sure you have data integrity,” says Mandy Ginsberg WG01, CEO of Match Group North America. So partner with a data scientist or two, in other words.

Anthony Noto, CFO of Twitter

Without doubt, another good person to partner with is your boss. Shedroff found his boss and mentor in David Eun, with whom he first worked at Time Warner Corp. in 2004 in New York City after finishing his MBA. When Eun left for Google, Shedroff followed him to the West Coast to join Google Video and manage its content licensing. When Google bought YouTube six months after he joined, Shedroff teamed with the new subsidiary, its 65 existing employees and a few other Googlers. He remained for another four years, managing relationships with professional sports leagues, Hollywood studios, broadcast networks and other corporate content creators.

He left to join a couple of startups—including Pulse, which LinkedIn acquired—but he ran into Eun again in NYC. Eun had joined Samsung in late 2011 and moved to Korea. He asked Shedroff if he was interested in working together again.

“I said, ‘Tell me what it is, and I am there,’” Shedroff remembers.

“The idea of working for and with people who trust you and whom you trust is so important. … Making sure you have people who are looking out for you and your career is important.”

Twitter’s Noto says much the same thing in the form of advice.

When professionals are in their 20s and early 30s, he says, their aim should be to find a position and a company that have the most “optionality”—wisdom essentially distilled into: find somewhere where your successes can greatly increase your chance of future

Twitter has been a convergence of all of his past successes and experiences—as a communication officer in the Army, a marketer for Kraft, then his Wharton MBA for Executives education and long Wall Street tenure, followed by the CFO role at the NFL and a return to finance with Goldman Sachs. For him, being a leader in tech is much the same as being a leader in any other sector: You have to have a vision and motivate individuals toward the execution and success of that plan. And to do so, you must understand those individuals’ professional and personal goals and align them with company success.

“That’s common whether it’s in the Army or Kraft Foods or the NFL or Twitter,” he says.

Meeting a boss like a Noto or a Eun—someone who will look out for your interests—may be easier in a new economy business—tech or tech-enabled. Ginsberg, who runs the largest tech-enabled dating business in the country, recounts a comment made by someone sitting on the plane next to her, someone who worked in a traditional industry, about having a great employer with an amazing executive team who came down from their offices to shake every employee’s hand right before the

“That’s an incredible story for me because if you look at SnapChat, Facebook, Google and, of course, Match … all of these businesses that have deep technology and product-facing organizations, the CEO and management teams don’t sit on another floor. They’re not coming down and shaking employees’ hands, they are part of the employee ecosystem and the culture,” she says.

3. Go Really Fast, Really Big

The D-word is at this point cliché, but it is a harsh fact that disruption is a survival-of-the-fittest fact in tech. It’s a high-profile space, explains Riley, so momentum is gained or lost by tech companies on a daily basis. It’s a race, a fight, for that momentum—in large part because a loss of momentum means a loss in talent, retained and acquired. Talent “flows” quickly, says Riley. It’s “huge stakes.”

“The pace and the change and the nimbleness that is needed in order to lead and stay a leader is profound,” says Ginsburg, whose first taste of tech came pre-Wharton, working with Microsoft as a client when she was at PR giant Edelman, where she came to lead the West Coast consumer Internet practice.

Noto has made decisions at high levels nearly his entire career, but he has more than ever needed to determine what are the most important things for the company, right now, and whether he has all of the right information to make the decision.

“I appreciate that now more than I ever have in my career,” he says.

“Twitter is a microphone for the world,” so decisions at Twitter have a “profound impact.”

He loves the mental and emotional challenge of being faced with decisions with “significant consequence,” which is good, considering he makes those every day. He likens the pace to sports—he played linebacker at West Point and three sports in high school—and for him, sports represented a new challenge and a new opportunity to have consequence on every “play.”

Another way to think of it is the need to take risks to keep ahead of the pace. It’s the ability to stomach that dynamic approach and the eagerness to embrace change. Galperin adds the word “creative” before the D—so that it’s not all about destruction. No, it’s “perfect competition,” making tech “really the most capitalistic industry.”

Galperin’s MercadoLibre hasn’t seen the meteoric growth rates in Latin America that some U.S. e-commerce giants have, but with growth at 20 percent to 30 percent per year over the long haul, that’s a success story revealing long-term staying power. He credits that to being able to change whatever’s worked, no matter how much it’s worked, every three to five years. MercadoLibre makes bets that sacrifice profits and growth in the here and now to be best positioned where technology will be down the road.

“Whatever disruption we see coming, we embrace it rather than resist it,” Galperin says.

If Galperin could change anything from his early days as a tech entrepreneur, it would have been to take even “bolder decisions sooner”—such as in buying companies to grow his business and hiring new talent around him.

“We had all these opportunities, and there’s only so much you can do with the team you have,” he says now. “Our mistakes would have been costlier, but our successes would have been greater.”

Being able to take risks also involves being OK with failure. Particularly when someone is young, being able to take calculated chances, fail, then learn and grow from it is a show of strength, says Ginsberg. Even from her position of leadership at Match, Ginsberg is willing to “fall on the sword” when necessary. She points to one initiative at Match, a big bet on a new advertising campaign, to which the company devoted resources, energy and hopes.

“I had to get up there months later and say, ‘It’s a bet we made, and it didn’t pay off the way we thought it would.’ And I think that having that honest dialogue and admitting when things don’t go according to plan is a very healthy dynamic in an organization like Match, where we’re providing such a personal service to our customers,” she says.

4. Entrepreneur: Inside or Outside?

For those who completely embrace risk—for whom failure isn’t even conceivable, let alone accepted—it may seem unhealthy to join an organization. Entrepreneurship—the paths of Riley, Galperin, and the new class of tech founders who grace magazine covers, appear on late night talk shows and have movies made about them—may be the only way to go.

Galperin admonishes those set on this tech path not to do so because they want to “work for themselves” or because they like risk. Only do so if you have a vision for something that no one else is providing.

“The glamour of doing a startup goes away very fast,” he warns.

Nicole Anasenes, CFO of Squarespace and a former CFO at IBM

Shedroff is one who believes entrepreneurship right out of school is a “risky way to chart a path.” His advice is to select an existing employer—preferably a growth company, though not necessarily a large company—where you can learn good habits and meet that quintessential mentor/boss. Take a role where you can pick up your head a couple years later having learned a skill or two and owned a project or two. Then you have a reputation that cannot be taken away from you, he says.

“To me, that’s the right jumping-off point when you get out of school,” he says.

For Ginsberg, entrepreneurship was in the family, with both her father and grandfather running their own businesses.

“When I graduated from Wharton and took my first job, my grandfather, who was a serial entrepreneur, did not talk to me for two weeks because he said, ‘I cannot believe you are working for someone else,’” she says.

But if you talk to Ginsberg, you get the sense for how entrepreneurial she has had to be in running the business of love. Monetization, marketing, customer experience, product road mapping, technology, staffing—she has been engrossed in all facets, making companies like Chemistry.com, The Princeton Review and Match her own.

That jibes with a point that Riley makes. Whether or not young aspirants try the startup route—and Riley is admittedly biased as a former entrepreneur and a board member for Wharton Entrepreneurship—they can broaden their definition of what it means to be entrepreneurial by considering an “intrapreneur” role at a larger company.

“It’s a powerful thing for business,” he says. “Most companies aspire to be entrepreneurial no matter how big they are.”

(Side note: As a former financier, Riley even gives his blessing to those who want to learn tech by handling its finance first on Wall Street. Noto also recommends his own finance-first path. A Wall Street career can expose someone quickly to how business, strategy and competition are done across a wide swath of the tech industry, they say.)

5. Don’t Worry About a Bubble

Nods to Wall Street aside, the tech industry is not just a faddish employment trend, not even for Wharton MBAs. Even companies in the space that we could consider established are still for the most part growing “tremendously fast,” as Galperin observes.

“It’s not like joining a bank or a retailer or an energy company that’s growing at single digits,” he says. These tech platforms are meant to change the world in many respects—remember?—and there’s still plenty of work to be done.

“We’re at a unique time, much like it was in 1999,” Shedroff says—in a good way.

Anasenes sees opportunity in that we’re experiencing the “consumerization of IT”—not just for, well, consumers but also for small and midsize businesses. Entrepreneurs are aiming to enable that end of the market with the same tools and services that enterprises now take for granted. She is meeting with many of these founders—seeking her next professional opportunity. She has been in the enterprise technology space for her entire career while building businesses within the context of larger businesses,

Anasenes explains, and now she wants to translate her big company experience to help grow an earlier-stage company. After careful consideration, she announced in early 2016 that she is joining online publishing services firm Squarespace as its chief

“Squarespace is the perfect fit for me. The team is phenomenal and passionate about helping to create beautiful websites and commerce experiences,” Anasenes says. “I see unlimited potential for Squarespace given the solid foundation CEO and Founder Anthony Casalena and team have already built.”

The overall advice for those interested in technology careers is: Go for it because it ain’t doing nothing but going up. Whether it is how technology is transforming most any other industry or how the “tech sector” itself will continue to evolve, “it is only going in one direction,” Riley says.

The delineation between the physical world and the virtual one doesn’t really exist. We’ve moved toward all technology, all of the time, says Ginsberg.

“I think we are going to stop talking about technology as a standalone thing, because it’s going to be integrated into every single industry and everything we do,” she says.

Galperin, who comes from one of the last classes at Penn to graduate without an email address, believes that the process of the Internet-ization of civilization could take 100 years. Whatever the timeframe, he feels we are still in early days.

“What keeps me motivated is to understand still the potential in the next 20 years is going to be as big as it was in the last 20 years,” he says. “I am excited as I have always been, probably more excited.”