When established companies explore opportunities to innovate, they typically consider strategies that fall into one of two well-known categories: incremental or disruptive. According to Wharton Professor David Robertson, they should be considering a third way: complementary innovation.

Complementary innovation refers to introducing a host of products and services that revolve around one core product, making that product more valuable and attractive to consumers. It’s a strategy that Lego has pulled off to great success.

But Robertson cautions that complementary innovation might not be a good fit for every company, as it presents a new range of organizational challenges that his research is still teasing apart.

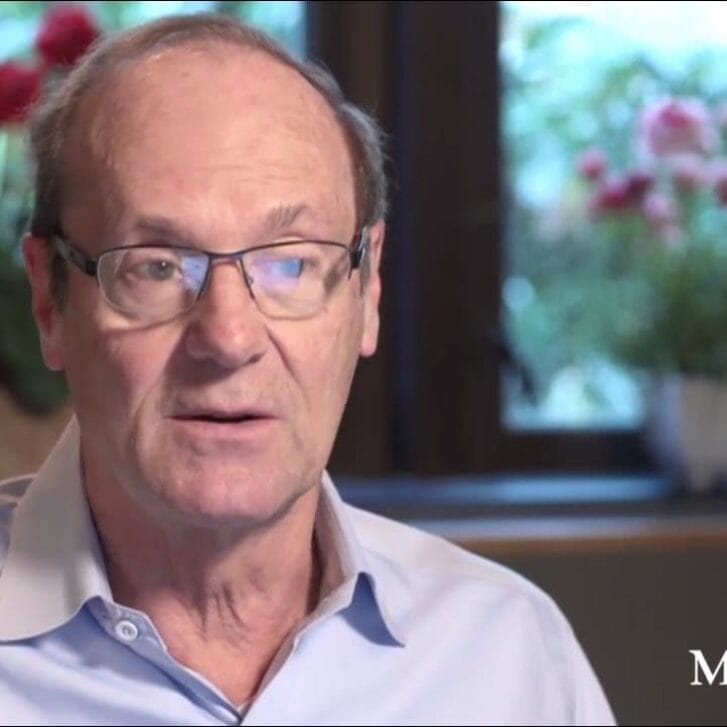

Robertson discussed this lesser-known innovation strategy in a 2015 interview with the Mack Institute. The video and a transcript follow below:

The Case for Complementary Innovation

So what I look at is innovation in larger companies in more established industries. I think there’s an awful lot of people out there who don’t have the freedom or flexibility to disrupt, to pivot or explore adjacencies. Their companies and their part of their companies are expected to offer a product to a market that expects and needs them to offer that product. And how do you innovate when you’re constrained like that? That’s what I’m interested in: How can we help those people become more innovative?

So if you’re in charge of a product line or a business unit that’s in an established company and an existing industry and you have to innovate, there are different approaches to that. We’re told that you can do incrementally better versions of your current product, or you can think outside the box and do big disruptive innovations. But I think there’s a third option that the best companies are doing, which is to innovate not inside the box or outside the box but around the box. How do you surround your current product with complementary products, services, business models, channels to market, that make that core product irresistible? Certain companies are doing that really well. But I think it’s not an easy or obvious type of innovation. And so that’s what I’m exploring now.

One example of a company that does this well—I wrote a whole book about it—is Lego. Lego is an easy-to-copy product. There’s no patent protection on the brick. Anybody can make one, and lots of companies do. And yet Lego’s profit margin is over 30 percent. Their average annual sales growth has been 20 percent every year for the last seven years, average annual sales growth is 20 percent and the average annual profit growth is 37 percent. This is a company that has no right to be this successful. But they’re doing that because they can innovate around the brick. They don’t just come out with a box of bricks, but they do lots of complementary innovations around that brick.

There are other companies that do that well too. USAA, in insurance, offers similar insurance products to what everybody else does. But they approach the business completely differently in terms of how they structure it and the way they deliver their services. And for that reason they’re doing tremendously well.

GoPro. GoPro was late to the market—not just for video cameras, but for action cameras. But they’re doubling in sales every year, not because they have a better camera, but because of all the things they do around the camera, like the mounts and the software. They’re even investing in drones. They’re coming up with their own line of drones that will carry their cameras around to give you better aerial shots.

Now those are examples of companies that innovate well around their core product. But what we’re seeing in the research is that doing that well requires a number of internal decisions to be made really carefully and thoughtfully. One of those is: Where are you not going to innovate? What is your core that you’re going to do yesterday, today and tomorrow? What products or services are you going to offer? And you have to be superbly good at that.

Once you’ve figured out what that core is, how are you going to innovate around that core so that you really enhance the value of that core to your customers?

And that moves companies in a very different direction. Often offering that really compelling set, that compelling family of innovations, of complementary innovations around the core, makes it externally really compelling, but internally really complex. And so managing it requires a whole different set of rules and processes and structures and metrics and everything else.

A lot of companies fall down there. They try and do this kind of external innovation with the same internal structure, and the whole thing falls apart. And so what we’re working on now is: How do the best companies make that happen? What problems have they had? What traps have they fallen into? And ultimately, what have the best ones done to succeed in trying to do that approach to innovation?

The research is fairly far along. We’re still working to understand what those processes are at each step so that it’s probably not the same recipe for each company. But maybe there’s an overall structure that you should follow if you want to try this approach to innovation.

And I should say that we’re not convinced that this is the approach to innovation that every established company must take, but rather if you’re going to innovate you should be looking at the next big thing, right? You should be looking at that—that disruptive new technology that may change your market. You also should be looking at how to make your current product incrementally better for your current customers. But also you owe it to yourself and your shareholders to explore other options for innovation. And so we’re exploring what those other options are and how you would do it.

One of the follow-up questions that we’re going to be exploring through the Mack Institute is to start looking at innovation centers in companies. One of the ways that companies try to boost innovation is opening up a corporate innovation center. And there are lots of different types of these, and some of them work better than others. The Mack Institute has funded some research for the coming year which is looking at corporate innovation centers, what works and what doesn’t, and how can those innovation centers help companies become more consistently and successfully innovative.

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on the Mack Institute website on Jan. 15, 2016.