As a native Spanish speaker, it strikes me as odd that we don’t have a word for procrastination. It’s not like we don’t experience it. I guess we just haven’t gotten around to naming it yet …

More seriously, one thing that’s interesting about procrastination is that we seldom postpone things for a long time. We don’t say, “I will start dieting next year;” we’ll always start “tomorrow” (crastinus means “tomorrow” in Latin).

Problem is, if you don’t start today, you won’t tomorrow, either.

We think of each individual decision to procrastinate as having very small consequences, but those decisions add up in a predictable way. In this first blog posting for the Wharton Blog Network, I wanted to share two ideas we can arrive at from this simple observation.

Idea 1. How do you know if you are procrastinating?

Leaving things for tomorrow is not always a bad decision. If your daughter is getting married, for example, doing your taxes next weekend is a wise decision.

But how do you know if your instinct to postpone something is good planning or just procrastinating?

Ask yourself this: “Is there any reason why doing this tomorrow would in any way be easier or less inconvenient than doing it right now?” If the answer is, “not really,” then “planning” is not what you are doing.

In other words, if calling the doctor tomorrow afternoon will be just as much of a pain-in-the-neck as calling her today, make that colonoscopy appointment right now.

Idea 2. How can you get others to stop procrastinating?

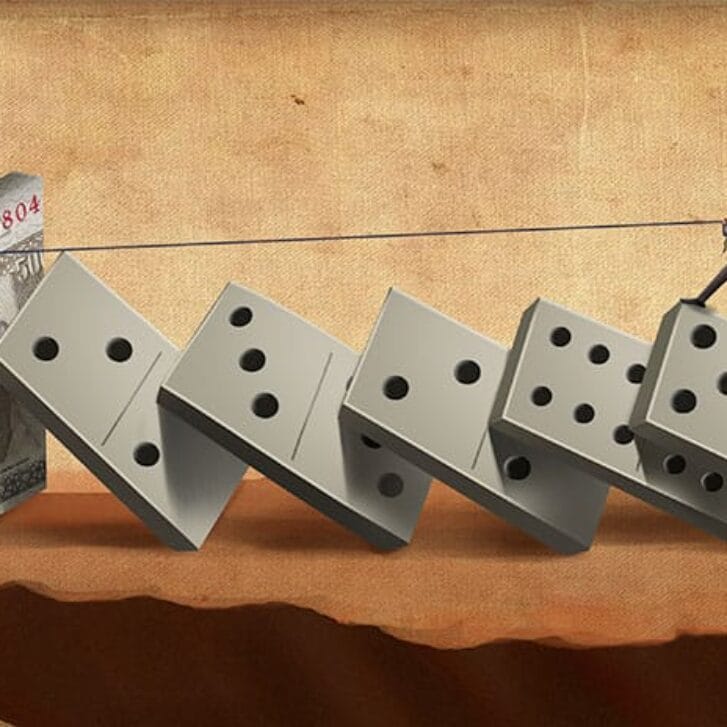

One thing I find interesting about big procrastination problems arising from many small procrastination decisions is that changing just one small decision could lead to fixing the big problem.

Here is an example I am testing with some colleagues.

A firm we are collaborating with has employees that need to pass an exam to remain employed. The exam is not hard, but it requires preparation. Many fail it. We, and the firm, think this is because employees always wait until “tomorrow” to start preparing.

Our solution is to pay them a little to start preparing “today.”

We will give some employees $5 (a favorable exchange rate on our side) to take the test within two weeks. Because they get three attempts per year, we don’t care if they pass it right away; we just want them to start thinking about it. We will compare their standing in the firm several months after our little experiment and see if a minimal investment of five bucks is saving the company thousands.

Will it work?

I’ll let you know.