“Our Friends Electric,” “Robots on the March,” “The Robots Take Over,” “How Technology Wrecks the Middle Class,” “How Technology is Destroying Jobs”—the doomsday headlines go on and on.

When so many similar articles on “collaborative” robots all appear at the same time, in (respectively) The Economist, The Hartford Courant, Wired Magazine, The New York Times Sunday Review and The MIT Technology Review, the conclusion is obvious. R2D2 and his friends are indeed banging at our door. Invited in or not, robots are about to be our inseparable partners, both at work and at home.

Since the dawn of electronic technologies in the mid-20th century, there has been a moral tension. Will these technologies turn out to be a benefit or a burden to society? To me, returning from World War II and seeing the technological advances it brought represented the step into my future. But to my father, who worked in the coal mines on his way to becoming a judge near Pittsburgh, PA, computers and automation meant only one thing: displaced workers and unemployment.

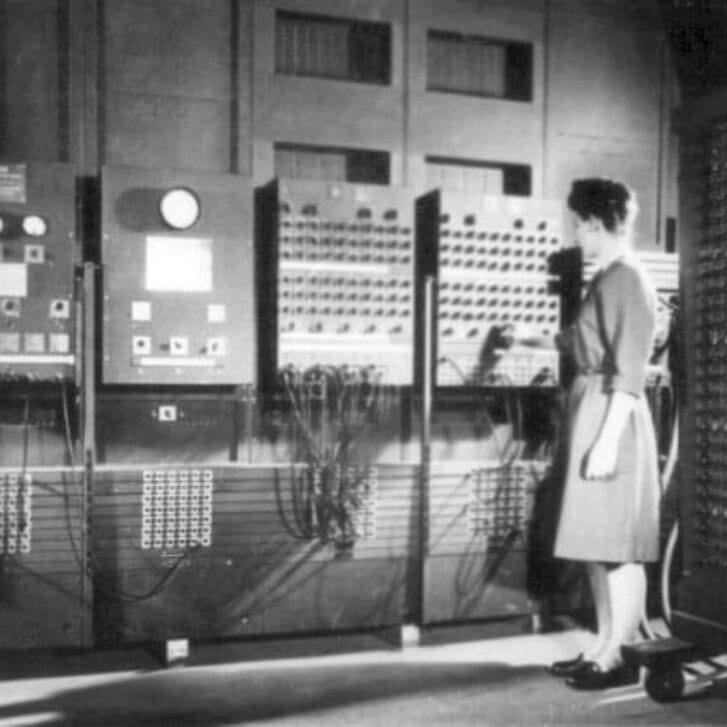

A classic photo of ENIAC, being used at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering (U.S. Army photo)

Penn and Wharton became leaders in shaping the continuously changing electronic world in 1946, when John W. Mauchly, HON’60, and J. Presper Eckert, EE’41. GEE’43, HON’64, first operationalized the computer ENIAC. And as one of the top business schools in the world today, Wharton must strive to harness and direct electronic and artificial intelligence to mold an economy in which both owners and stockholders will benefit as technology becomes the platform for improving the quality of life for all.

But this can only be accomplished at the expense of other stakeholders in our economy, most of all, the workers and consumers. This new robotic phase of technological change requires making agonizing value-choices.

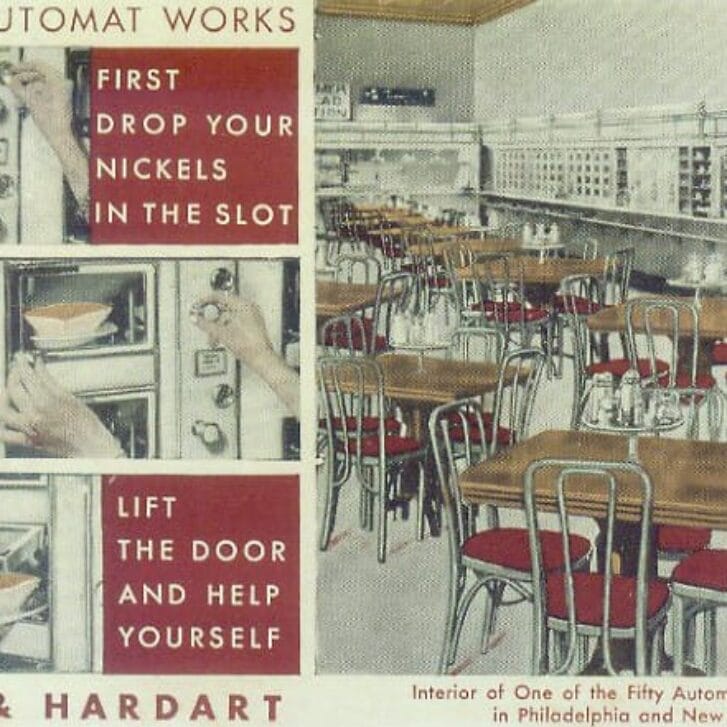

Robots and artificial intelligence have been a part of our work and personal lives for some time. Sometimes they have been way out front, as in the automobile production lines. At other times, they remain invisible, in Wall Street offices, at point-of-sales credit card devices, at ATMs, at airport boarding pass terminals, at every Internet-based retail transaction we undertake and even in our kids’ toys.

With greater sophistication, they are also becoming more visible and “co-operative,” like R2D2 in Star Wars and with such friendly names as well: Baxter, Atlas, Aismo, DaVinci, Kiva, Aist and “Care-O-bot.”

Wired magazine’s Kevin Kelly predicts that to be successful, everyone will have to learn to have a robot as a partner, like it or not. MIT Technology Review’s Editor David Rotman makes the same prediction. But where Kelly is optimistic about the future for human employment in a robot-based economy, Rotman fears that the future job picture is dismal, particularly for the middle class. His fears are shared by other economists, technology experts and labor leaders.

Can more robots lead to a more productive economy without reducing the wealth status of the middle and working classes in our economy?

That is the issue Wharton’s faculty and graduates face as they maintain their leadership role in developing the continually changing electronic society.