The content at Wharton Magazine is sometimes derivative. By that I mean alumni will reach out in response to an article with their own story to share. In many cases, those are some of the best stories that we come across. My evidence today is Howard Kroplick, WG’73, and his racecars.

Our connection with Kroplick began when we published our Wharton Watch List for the fall 2013 issue. The topic: members of the Wharton community with some of the most massive and/or engaged social media presences. (Read the Watch List but be sure to come back for this story.) In response to the Watch List, Kroplick sent an email to Wharton Magazine. He explained how he had created Vanderbiltcupraces.com, “an automotive racing history website that received a 2013 Webby Award as ‘one of the five best in the world for car sites and car culture.’ ” He included links to the articles on the site and, better yet, videos—such as the one below of him driving the 1909 Alco Black Beast Racer on “Legends Day” at the 2012 Indy 500.

As you saw in the video, other classic cars moving at 150 mph passed the Black Beast at twice Kroplick’s speed.

“It was the most exhilarating and terrifying thing I did in my life,” Kroplick told me when I responded to his email with a phone call.

His drive to create Vanderbiltcupraces.com came from two intermingled passions: cars and history. The former began with his first automobile, a 1966 Mustang that was lost, like his bachelorhood, when he married. (He didn’t get another until 2004, when his wife told him to stop bothering her about the first and he bought a Shelby Mustang at a Christie’s auction; he now has three, including a ’66.) With history, Kroplick got involved when he discovered one of the Vanderbilt Cup Races passed close by his home on Long Island.

“The cup was the Super Bowl of its day for racing,” Kroplick said.

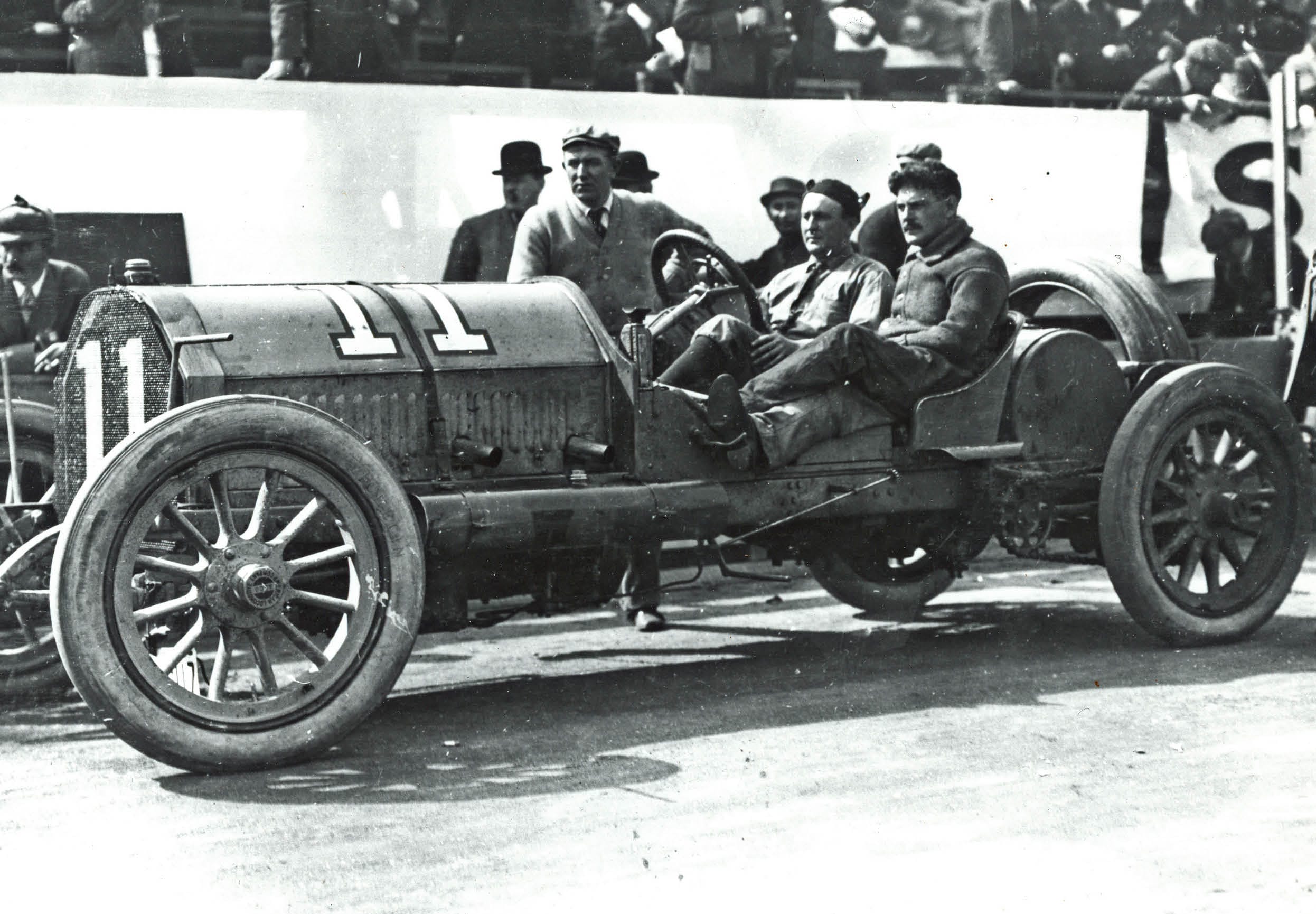

Five years of research about the race at the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum and the purchase and restoration of one of the real Vanderbilt Cup Race cars—the Alco Black Beast, winner of the 1909 and 1910 Vanderbilt Cup Races and favorite in the first Indy 500 held in 1911—led to a book on the races and the website in 2008, which Kroplick set up with his daughter in part to promote the book.

The site has earned him fame in the car history world. He and the Black Beast were invited not once but twice to the Indy 500. (The second time is recorded in the above video; the first time is in 2011 when racing legend Emerson Fittipaldi drove the car with Kroplick along as the passenger.) He also earned a spot in an episode of History Channel’s Men Who Built America, playing Alexander Winton in a re-enactment of his 1901 “Race That Changed the World” against Henry Ford.

http://youtu.be/SOsP9m5-6Uo?w=530

Through the site, descendants of Vanderbilt Cup Race drivers can get in touch with the historian as well, seeking information about their loved ones.

“It turns out that I have more photos of their relatives than they do,” Kroplick told me.

One relative of a driver asked him for an email address for a commenter on Vanderbiltcupraces.com, who turned out to be a second cousin. They hadn’t seen each other for 60 years.

If we ever do a Wharton Watch List about historians, we’ll be sure to contact Kroplick. Not only is he the expert on the Vanderbilt Cup Races, he has written a book about the Long Island Motor Parkway, the first highway built for automobiles, and has another on the way about North Hempstead. He is in fact the official town historian for that Long Island community.

Whenever we do another article about the pharmaceutical industry, we will probably contact Kroplick again for that, too. He worked at Pfizer in product management for nearly a decade before setting out on his own to found a Manhattan-based medical education communications firm, The Impact Group, which he grew into a 150-person agency and sold. His insider stories about Big Pharma in its heyday may be as colorful as his stories about the Black Beast, particularly when he starts talking about his role in the launch of Viagra.

Some of Wharton Magazine’s best content is derivative, as I said earlier.