During the 2008 financial crisis, the American public began to hone in on the practices of investment banks as epitomizing greed on Wall Street. As reports of bank bailouts and home foreclosures began to trickle out, the veil of mystery surrounding the activities of investment banks was slowly lifted.

A growing number of investment banks, which were initially formed as small partnerships to provide strategic corporate advice and financing services, had evolved into sprawling financial “supermarkets” that were continuously implementing new strategies in search of additional revenue streams.

The result? “Financialization” of the American economy.

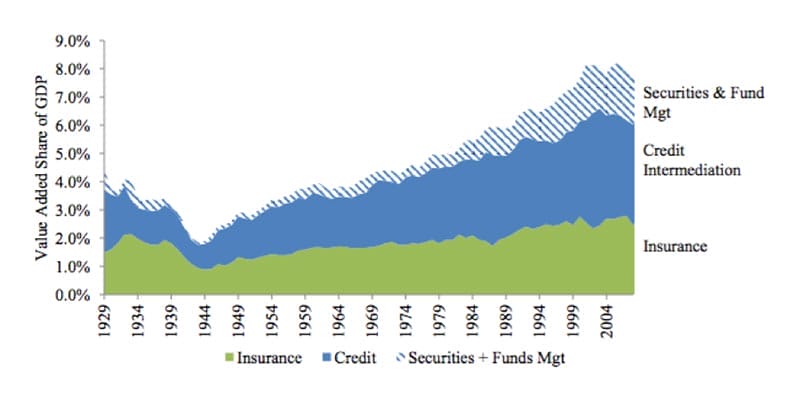

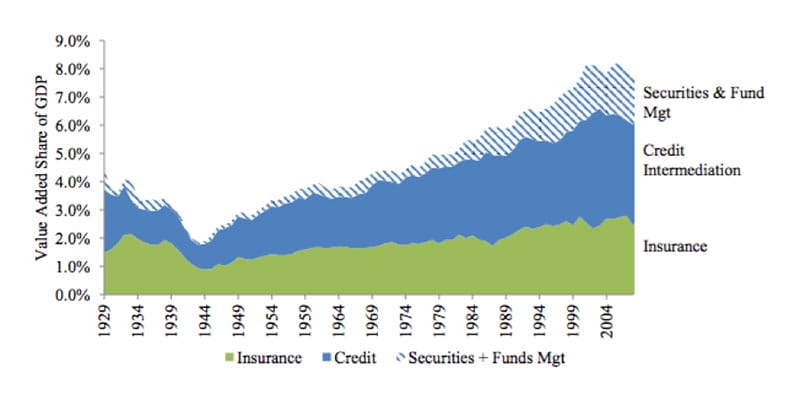

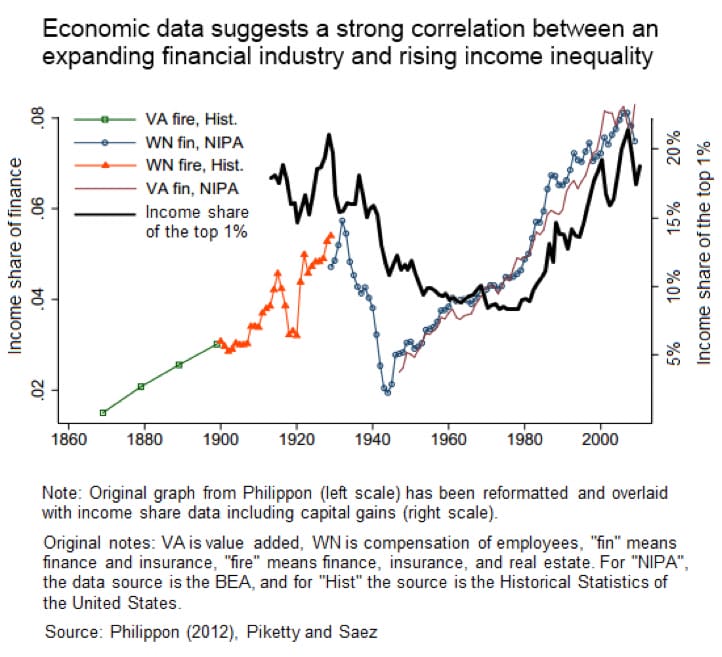

In 1980, the financial services industry accounted for just 4.9 percent of U.S. gross domestic product compared with 7.9 percent in 2007. Over that period, the ratio of total financial assets to GDP in the U.S. more than doubled, from five to 10. Main drivers of modern finance’s growth included increasing asset management fees, expansion of household credit and development of the “shadow banking” system.

The rapid increase in the size, power and profitability of American financial institutions has caused some to question this financialization and its benefit to society.

Regulatory Barriers Up and Down

Historically, the main purpose of a bank was to match savers with borrowers. Banks served as financial intermediaries, paying interest on deposits while also making loans to businesses and consumers. Fl The rise of computer technology and the increasing competition on Wall Street have forced financial services firms to innovate at a wild pace to engineer new financial products.

The transformation of traditional financial services firms into large, diversified financial “supermarkets” is closely related to the history of government regulation and subsequent deregulation. After the stock market crash of 1929, the Glass-Steagall Act was implemented to reduce systemic risk by forcing the separation of commercial banks from securities firms.

Well-known financial institutions such as J.P. Morgan were forced to spin off their investment banking units (i.e., Morgan Stanley) in order to comply.

Beginning in the 1980s and continuing through the 1990s, however, many of these regulations were phased out and commercial banks began to again merge with securities firms to provide a full suite of financial services to their clients.

One of the largest growth areas for these new financial megafirms became asset management, which generate huge fees for their parent companies.

Asset Management

In recent years, there has been a push to transfer assets to professional money managers who charge a percentage of assets under management to actively manage investments on behalf of a client.

According to data from the Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States, professional managers managed 53 percent of household equity portfolios in 2007, compared with only 25 percent in 1980.

In addition to this factor, the growing popularity of alternative investment funds—private equity, hedge funds and venture capital—which typically charge much higher fees than traditional mutual funds, has caused asset management fees to hit all-time highs.

Some have said that benefits of having more capital allocated to asset management firms include increased stock market participation, enhanced liquidity and more efficient markets. Others, however, feel that the growth of the asset management industry has led many to overpay for active asset management services.

In addition, other critics claim that high wages and fees not only lure top talent away from arguably more socially valuable careers but can also contribute to rising income disparities.

Household Credit

Another area of growth has been the rise in household credit in the form of mortgage debt. Mortgage backed securities (MBS), an innovative financial product developed by investment banks, have greatly increased the amount of capital available to borrowers wishing to purchase a home. This, in turn, has led to higher rates of home ownership.

By packaging or “securitizing” large amounts of mortgages into one security, investment banks have been able to tap into a much larger pool of potential investors for home loans.

Although proponents of securitization have argued that innovative financial products such as MBS have enhanced liquidity in the marketplace, others have said that the demand for these products led to the lenient lending practices that resulted in the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis.

Shadow Banking

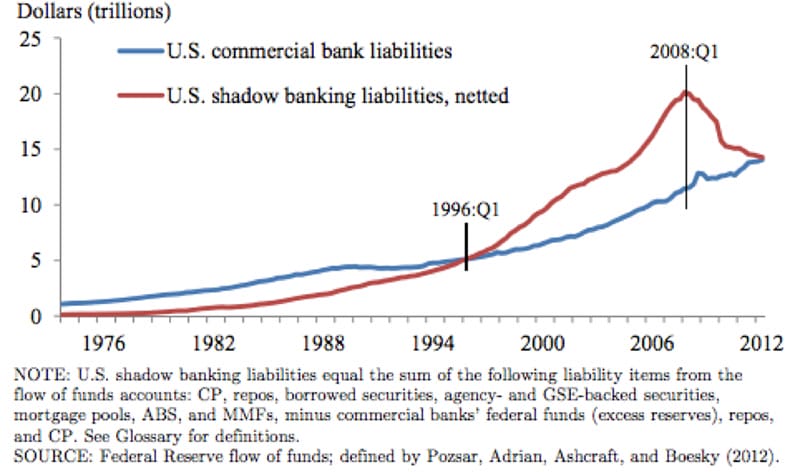

The development of the “shadow banking” system has also fueled the industry’s growth. Shadow banking has been defined as banking “without access to central bank liquidity or public sector credit guarantees.”

Shadow banks such as hedge funds, investment banks and structured investment vehicles have come to provide traditional banking services—originating loans, for example—without having to comply with the same regulations as depository banks.

Although the rise of the shadow banking system has led to an increase in market participants and liquidity, the inherent lack of regulatory oversight in addition to the interconnectivity and interdependence among less regulated entities has caused many to question the fragility of the system.

The spectacular growth of the financial services industry has generated both positive and negative consequences for society.

During the 2008 financial crisis, many Americans became aware for the first time of the increasing influence that Wall Street firms had over normal financial activities like taking out a mortgage. After the crisis, the government enacted the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act to bring substantial changes to financial regulation in the U.S. Despite this, the financial services sector has continued to grow.

The growing power and influence of financial services firms has certainly increased market participation and liquidity, but let’s continue to closely monitor potential risks that could lead to future market meltdowns.

Dan Miller is co-founder and president of Fundrise.