The air is thin and the tea is tepid at the Himalayan village of Chukhung, nestled at 15,584 feet among an array of the world’s greatest mountains. We’ve been climbing since 3 a.m., roused from our slumber by our head Sherpa, Ang Jangbu, a Mount Everest veteran. The objective today: a peak more than 2,000 vertical feet above the village whose views, says our guidebook, are “staggering.” The early morning sun is warming the air and lighting the summits. We’re pumped.

We are reaching the high point of our two-week “WEMBA Leadership Trek to Mt. Everest.” The night before we had slept fitfully near the hamlet of Dingboche, at 14,270 feet the highest permanent settlement of the region, its treeless plateau already placing us at an elevation near the crest of the Swiss Alps. The day before, our team of 19 trekkers had been jarred by a potentially serious case of altitude sickness. But now we’re feeling fit, and one of the world’s great panoramas beckons above.

We have organized this trek in the Himalayas’ famous Khumbu region to stretch our imagination and expand our working concepts of leadership and teamwork. One of us — Mike Useem — has been teaching the WEMBA (Wharton Executive MBA) leadership course during the past several years, and the other — Ed Bernbaum — has been researching the role of mountain metaphors in leadership and organizing treks through India, Nepal and Tibet for many years. Together, we’ve sought to create a unique learning experience for WEMBA graduates who are looking to deepen their mastery of personal and team leadership.

The Himalayas offer a unique environment for continuing personal development. Mountain climbers, like the mountains they climb, hold a central place in our culture’s mythology, a paradigm for how individuals striving to reach a goal can achieve what others label impossible. But reaching a summit is usually far more than personal achievement, for it almost always depends on collective effort, with the contribution of each required for the success of all.

Trek Readings

We converge on Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, a few days after Penn’s 1998 commencement ceremonies. Arriving by air from destinations as diverse as San Francisco and Santiago, we each complete a landing card whose choices for arriving must be unique in the world: “holiday pleasure,” “trekking,” or “mountaineering.” The next morning we’re back at the airport for a 7 a.m. flight to Lukla, a tiny tilted runway built by Sir Edmund Hillary on a high plateau as a gateway to the Mount Everest region. The choice of domestic airlines leaves no doubt where we are: Mountain Air, Buddha Airways and Everest Air.

The pilot aims his aircraft at the Lukla runway and his angle seems better for dive-bombing than safe-landing. At the last second, however, he pulls up, we drop onto the gravel surface, and a minute later we find ourselves at 9,320 feet among a swirling multitude of trekkers and Sherpas.

Before setting forth up the trail to Mount Everest, we assemble for a “before” photograph featuring 11 recent graduates of the WEMBA program: Mun Fenton, Jan Hartmann, Anne Libby, Leontina Marcotulli, Randy Ment, Evelyn Nagel, Daniel Neal, Anita Orellana, Sara Sutherland, Tim Urekew, and Chris Witt. Besides the two of us, they are accompanied by two brothers, Eugene Nagel and Pedro Orellana; a sister, Marialidia Marcotulli; a former WEMBA student employee, Sabrina Lowe; a faculty member, Peter Dean; and a daughter, Andrea Useem.

Disparate motives have brought us together. One participant intends to conquer the high anxieties of his workplace by mastering the high altitude challenges of the trek. Another seeks the opportunity to explore management issues in an environment totally different from the daily routine back home. A third is looking for a “once in a lifetime experience,” and a fourth says she wants to learn more about leadership. A fifth person confesses that he’s come in part as a reconnaissance for a possible climb of Mount Everest.

To make the most of our itinerary, we have prepared a 16-page trek “syllabus,” a detailed outline of our daily destinations and trailside seminars. Each day of the trek, two of the participants assume leadership responsibilities, explaining our destination, assigning trail tasks and organizing special events. We’ve already steeped ourselves in mountaineering narratives and studies of Eastern cultures, digesting a list of trek readings and even a “bulkpack” with excerpts on cross-cultural leadership, Tibetan Buddhism and Sherpa society.

Trekking and climbing provide evocative metaphors for transcending challenges and attaining goals. During mid-day and evening seminars for the next 10 days, we use a range of topics to reflect on our personal and team leadership. From “Responsibility Under Extreme Stress” and “Divergent Concepts of Leadership and Teamwork” to “The Buddhist Path to Awakening” and “Alternative Paths to the Top,” we ask ourselves a number of questions:

- Can the mysterious hidden valleys of Tibetan lore, some resembling the fictional Shangri-La of James Hilton’s novel, Lost Horizon, offer fresh insights into the meaning of leadership and teamwork?

- Sherpas traditionally elect people to serve as village heads only if they do not aggressively seek the position. Anybody who wants the job for personal benefit is viewed as unfit to serve the community. How do non-Western ways of approaching authority reveal different possibilities of leading and working together as a team?

- In the first American expedition to Mt. Everest, one group chose the unclimbed but riskier West Ridge, a second group the previously climbed but more certain South Col route. What motivated the teams to take such different approaches, and, in turn, what distinctive forms of leadership and teamwork did each require?

- What went right — and what went wrong — on the fateful day of May 10, 1996, when three climbing expeditions, all nearing the summit of Mt. Everest, were hit by a violent storm?

- What does it mean to attain a summit? How can we incorporate the experience into the rest of our lives? What should be next?

Trailside Classroom

Our day begins around 5 a.m. with Sherpas and Sherpanis serving tea and coffee through the front flap of each of our tents, followed by basins of hot water for washing. Break-fast ranges from bacon and eggs to oatmeal and pancakes. Other meals are equally lavish, if sometimes heavy on rice and noodles. We also sample the local staples: small boiled potatoes dipped in salt and tsampa — roasted barley flour mixed with butter tea into a thick paste.

Our day begins around 5 a.m. with Sherpas and Sherpanis serving tea and coffee through the front flap of each of our tents, followed by basins of hot water for washing. Break-fast ranges from bacon and eggs to oatmeal and pancakes. Other meals are equally lavish, if sometimes heavy on rice and noodles. We also sample the local staples: small boiled potatoes dipped in salt and tsampa — roasted barley flour mixed with butter tea into a thick paste.

On the fifth day our leaders propose organizing us into three groups dubbed “power walkers,” “photo freaks” and “conversationalists.” The breakfast discussion, however, reveals that almost everybody is opting for the third. Our leaders revise the scheme, and soon a first group sets off under the new name of “Save our Power” to signify a strategy of moving fast but efficiently. They are followed by “Contemplation with Stimulation,” whose charge is to talk about what they see, and at the back is the “Funeral Procession,” whose ironic motto — “Arrive Alive” — questions the others’ strategies for the day.

The power savers report at our lunch seminar that they experienced a “religious” problem on the trail. Sacred mani stones carved with prayers frequently appear trailside, and Buddhist tradition requires that passers-by keep them to the right. Occasionally the rugged terrain necessitates circuitous paths to abide by the custom. One of the power savers refuses to take the long way around, asserting he was doing so in the name of the group’s goal of saving energy. His companions decide to penalize him for his cultural infraction: he will have to cede each a chocolate bar.

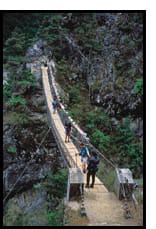

As we wend our way higher, bamboo and pine give way to rhododendron and juniper, followed by no forests at all. We cross deep gorges on footbridges, some solid, others rickety or swaying over seething torrents. Often we share the narrow crossings with heavily laden yaks, and when they are coming toward us, their sharp horns stretching from handrail to handrail, they always win.

On our way to Dingboche, our highest campsite of the trip, one trekker becomes nauseous and dizzy following the sudden onset of a splitting headache — classic symptoms of life-threatening altitude sickness. After several hours of further ascent, we decide that immediate descent is essential, and he returns with a Sherpa to a trailside clinic specializing in mountain sickness. We lament the loss of a team member — the camaraderie already matches that of a summer camp — but he fully recovers in the thicker air at 12,369 feet and goes on to have experiences as rich and rewarding as ours. The Sherpas draw him into their culture and reveal an artifact from the Himalayas’ X-files: the scalp of a yeti, the abominable snowman.

On our way to Dingboche, our highest campsite of the trip, one trekker becomes nauseous and dizzy following the sudden onset of a splitting headache — classic symptoms of life-threatening altitude sickness. After several hours of further ascent, we decide that immediate descent is essential, and he returns with a Sherpa to a trailside clinic specializing in mountain sickness. We lament the loss of a team member — the camaraderie already matches that of a summer camp — but he fully recovers in the thicker air at 12,369 feet and goes on to have experiences as rich and rewarding as ours. The Sherpas draw him into their culture and reveal an artifact from the Himalayas’ X-files: the scalp of a yeti, the abominable snowman.

Each night our trek physician runs a standup clinic for aches and pains. Sore muscles are few, for we have all conditioned hard before the trek. Several hired professional trainers, and one even spent hours on a treadmill with climbing boots and loaded backpack. Sore or not, we are all tired from the day’s trek, and most of us will be fast asleep by 9 p.m. Save the occasional roar of an avalanche off a nearby peak, the only sound is the tinkling of bells from pack yaks.

Soda and Prayer Wheels

The warden of Sagarmatha National Park, Nyima Wangchu Sherpa, joins us for dinner in Namche Bazaar, the crossroads of the region. His park encompasses Mount Everest and its environs, and he notes the rapid growth of foreign visitors, from 4,000 in 1982 to 17,000 last year. The abbot of Khumbu’s best known monastery at Tengboche, however, is unfazed by the rising tide. When we ask if his monks are sometimes distracted by the backpacker wealth passing their prayer wheels, he responds that if so, they do not understand Buddhism.

Start-up possibilities in our desolate terrain are not so evident to the unaided eye, but through the prisms of newly minted MBA graduates, we can see that they abound. What better way to promote a local soda than to name it after the roaring glacier-fed river along which we’ve been walking for days, the Imja Khola. Another possibility: Spinning a Buddhist prayer wheel clockwise says a silent mantra — Om Mani Padme Hum, hail to the jewel in the lotus — and we have seen stream-spun wheels along our trail. For the many prayer wheels without stream power, however, why not introduce high-tech solar cells to spin them, generating blessings throughout the region? A third possibility: Few of the region’s peaks are presently named. Adjacent to Mount Everest, for instance, are peaks 7708, 7804, and 7143, identified only by their height in meters. Surely we can raise millions of rupees for Khumbu Sherpas by offering to name the mountains after particularly generous donors. But we learn that among Sherpas, summits are reserved for deities, and gracing peaks with the names of mere mortals would demean them. Even Mount Everest, honoring the British surveyor, Sir George Everest, is known by the Sherpas as Chomolungma or Jomolangma, the name of a Tibetan goddess of long life and prosperity. We are reminded of the pitfalls of selling across cultures we do not yet fully understand.

A third possibility: Few of the region’s peaks are presently named. Adjacent to Mount Everest, for instance, are peaks 7708, 7804, and 7143, identified only by their height in meters. Surely we can raise millions of rupees for Khumbu Sherpas by offering to name the mountains after particularly generous donors. But we learn that among Sherpas, summits are reserved for deities, and gracing peaks with the names of mere mortals would demean them. Even Mount Everest, honoring the British surveyor, Sir George Everest, is known by the Sherpas as Chomolungma or Jomolangma, the name of a Tibetan goddess of long life and prosperity. We are reminded of the pitfalls of selling across cultures we do not yet fully understand.

Leadership Lessons

Leadership involves developing a vision, articulating a direction, and inspiring others to achieve it. We have designed the trek to explore how mountain metaphors, Eastern as well as Western, can be used to build both personal and team leadership. As our discussions and experiences intensify in the rarefied atmosphere and stunning scenery, enduring lessons emerge. Build your leadership: Arlene Blum organized an expedition of premier women climbers to climb Annapurna in 1978, but she found her decisions on the slopes frequently questioned by her team members. A formal position invests you with little real authority, we conclude. You must earn the confidence of those you expect to lead, and it is best acquired well before you’re on the mountainside. Explaining your purpose, demonstrating your capacities, and obtaining buy-in are among the steps required, and our two daily leaders seek to display all when initiating their agenda for the trail.

Build your leadership: Arlene Blum organized an expedition of premier women climbers to climb Annapurna in 1978, but she found her decisions on the slopes frequently questioned by her team members. A formal position invests you with little real authority, we conclude. You must earn the confidence of those you expect to lead, and it is best acquired well before you’re on the mountainside. Explaining your purpose, demonstrating your capacities, and obtaining buy-in are among the steps required, and our two daily leaders seek to display all when initiating their agenda for the trail.

Challenge your leaders: We meet one of the lucky survivors of the May 10, 1996 disaster on Mount Everest, Sandy Hill. She reports that one of her great regrets was not having questioned the condition of her climbing leader, Scott Fischer, whose impaired health stranded him on the summit ridge when the violent storm hit. Although members of his expedition had reached the summit, he insisted on continuing up — and he never returned.

Stay centered: A noontime discussion of Buddhist ideals and practices at the foot of a ridge leading up to the Tengboche Monastery points to the practical value of cultivating a sense of inner serenity, of deflecting distractions. One participant recalls a boss who was decisive and calm even at moments of “total chaos,” and others confirm the point with their own accounts of managers whose confidence in the face of conflict kept the organization on course.

Distribute your leadership: Near the end we share examples of leadership we’ve witnessed along our 80-mile trek. Many single out Ang Jangbu, our head Sherpa, who has flawlessly delivered us to the slopes of Everest with a large team of Sherpas arranged through our outfitters, Geographic Expeditions and Great Escapes. The Sherpas always seemed to know what to do. Jangbu “handled everything very quietly and efficiently,” recalled one participant, “managing our Sherpa staff without a fuss.” He also infused our mobile multitude with an implicit but ever present leadership: “You never saw him actually leading,” said the observer, “but whenever you needed him, he was always there.”

Incorporate divergent intents: On leaving the village of Chukhung, many choose to go for the summit above, others to admire the view from a hill on its slopes. Both objectives fit the trek’s agenda of achieving each member’s goals. “I had come for the view and the sights,” said one of the participants, “and even on that hill I got it. I relaxed, I was enjoying myself, it was a beautiful day, and feeling good sounds like a good finish to me.” Persistence pays: After several hours of arduous climbing above the village of Chukhung, those who chose to go to the summit finally achieve the trek’s intended high point, Chukhung Ri at 17,772 feet. Personal and collective determination have made the difference:

Sara Sutherland: “I hit a major wall 2,000 feet ago. I looked up and couldn’t do it, but Dorje [one of our Sherpas] said, ‘Take small steps and you can do it.’ So I dumped my pack, ate an Ironman bar and started up.”

Anita Orellana: “I wanted it so much that I didn’t stop to think that I wouldn’t be able to do it. What helped me was to keep a regular pace and to stick together. We were all pushing together.”

Daniel Neal: “I noticed on the way up that every single step counted, every one. It’s amazing how all these little steps, every little muddy gritty step, resulted in this marvelous vista.”

The view is as spectacular as the guidebook has promised. We look across at Ama Dablam (“Mother’s Charmbox”), a 22,493-foot Matterhorn-like spire, and at Makalu, the world’s fifth highest mountain at 27,790 feet; behind us rises Lhotse, the fourth highest at 27,890 feet with a two-mile vertical face, capped by the highest overhang in the world. The 360-degree panorama is mesmerizing, but the gaze of Tim Urekew is riveted on just one point of the compass: a still higher pinnacle rising behind us. Given the thin air and exhausting ascent, the rest of us are more than content with our present perch. But within minutes, we’re stirring again, and an hour later, we’re standing at 18,238 feet above sea level, lost in wonder at the magnificent panorama and the path that placed us there.

Michael Useem is William and Jacalyn Egan Professor of Management and Director of the Center for Leadership and Change Management at Wharton; he is author of The Leadership Moment: Nine True Stories of Triumph and Disaster and Their Lessons for Us All (1998). Edwin Bernbaum is Senior Fellow at The Mountain Institute and Research Associate at the University of California at Berkeley; he is author of Sacred Mountains of the World (1998) and a frequent lecturer on mountains, creativity and leadership.