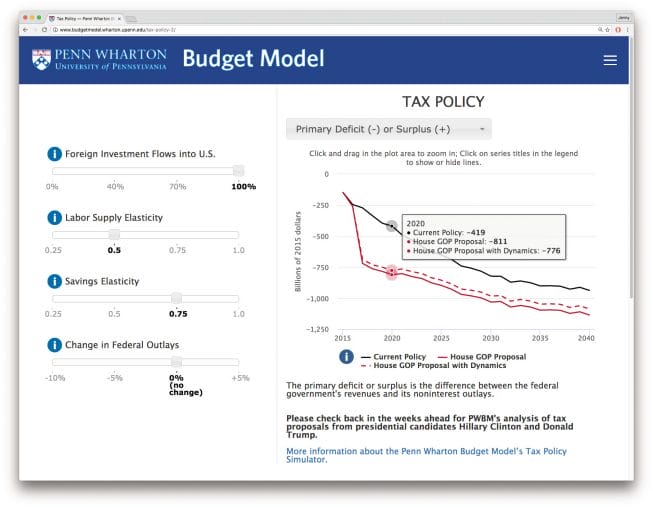

The National Budget affects all aspects of American life—education, housing, retirement and health care, to name a few—yet for most of us, the budget-making process and its impact are a mystery. A new economic modeling tool from the Penn Wharton Public Policy Initiative encourages anyone to play policymaker for a day. The Penn Wharton Budget Model allows users to simulate the economic impact of national budget policies online and for free. This nonpartisan fiscal sandbox doesn’t advocate for specific policies; rather, it encourages users to experiment with ideas and tweak the data to produce upwards of 4,000 outcomes.

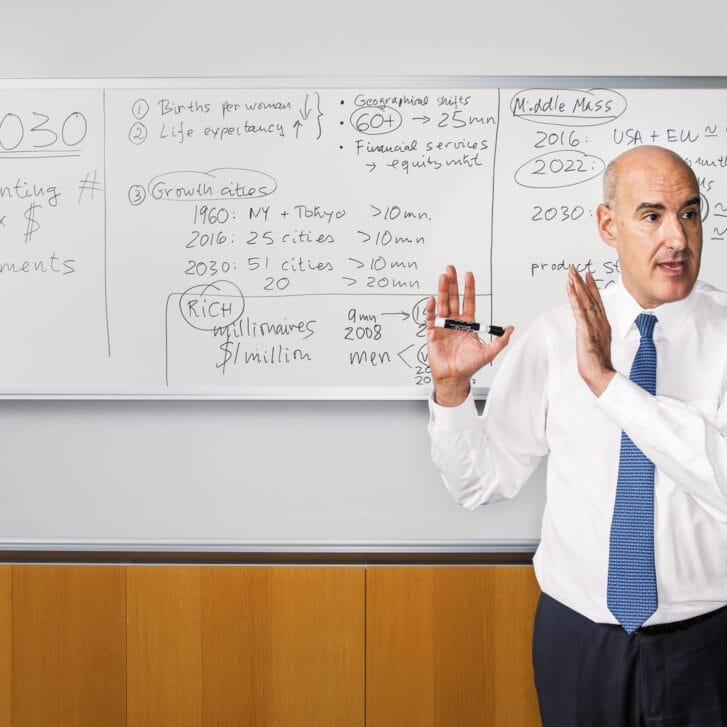

Led by Wharton Boettner Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy Kent Smetters, a team of 13 technologists and economists unveiled Social Security and immigration modules in June, followed by a tax reform module in September. Seven additional interactive graphs—on health care, retirement policy, housing finance, criminal justice, education, aggregate risk management and retirement—will be released in the coming year.

The PWBM shows 125 policy combinations on immigration and 4,096 combinations related to Social Security. The immigration simulation allows users to adjust policies affecting skilled immigrants, annual legal immigration and number of deportations to test the impact on indicators such as population, employment and gross domestic product—a timely topic, given the debate playing out in this presidential election cycle. For the Social Security module, users can toggle dials to control policies such as the payroll tax rate, the retirement age and across-the-board benefits to see the impact on measurements such as trust fund reserves, Social Security taxes and interest income.

This transparent and easily accessible tool brings facts back into conversations about important national issues. Journalists can research politicians’ platforms. Voters can learn about issues that affect their daily lives. Professors can demonstrate economic concepts to students. And perhaps most importantly, decision-makers can test ideas before drafting legislation. “We’re trying to show policymakers different options to explore before they actually have their bill together,” Smetters says. “That’s what policymakers have been telling us they’re eager for.”

No Taxation Without Evaluation: The tax policy model allows for a close look at both the nation’s economy (GDP, capital services) and the federal budget (revenues, Social Security/Medicare, deficit and surplus).

Economic analysis is often one of the final steps in turning an idea into law. That process can be frustratingly backward, as policymakers commit to an idea before receiving crucial information about its economic impact from an organization like the Congressional Budget Office, which produces cost estimates for nearly every bill approved by Congressional committees. The PWBM interrupts this process with what those policymakers are hungry for: a way to test predictions.

The PWBM doesn’t aim to replace projections made by government agencies, but rather simply to offer more information at an early, critical moment. “It’s a great tradition we have in America, to have independent government organizations to aid in the political process,” Smetters says. Smetters and his team responded to the needs of policymakers who eagerly sought more analytics than the late-stage data from CBO. “Now it’s not just ‘I have an idea. Let’s try to get some official evidence.’ It’s really about ‘I want to cut across hundreds of ideas in one sitting and look at the different branches of possibilities,’” Smetters says.

Objective nonpartisan data and economic analysis can help policymakers and the public separate ideology from facts in order to make informed and thoughtful decisions. That intersection of data and its analysis is right in Wharton’s wheelhouse. “Wharton has a strong reputation for using rigorous data analysis and applying that to fact-based business decision-making,” says Kimberly Burham, PWBM managing director of legislation and special projects.

Wharton alumni representing a broad political spectrum fund this project and sit on the advisory board. The funders—Stewart Bainum, S.A. Ibrahim WG78, Marc Rowan W84 WG85, Marc Spilker W86, Leonard M. Tannenbaum W93 WG94, David Trone WG85 and George Weiss W65— sought to create a mechanism to share Wharton’s strengths in economic analysis in order to fuel data-driven decisions in Washington, D.C. Scott Wieler WG87, founder and CEO of Signal Hill Capital Group, believes the tool shows how business can be a force for good in the world. “To me, this tries to show policymakers how you could you use the tools and analytics that are available at Wharton’s disposal,” he says.

The PWBM aims to cut through the political hyperbole and give all sides a common footing in data. “Republicans and Democrats are far apart on a lot of different things,” Wieler says, “but they’re probably much closer than they think on a few issues. If you can isolate the policies they’re close on, we can really move forward.”

Managing all the possible combinations requires tapping into the latest technologies. “The model brings the best of advances in economic modeling, big data and cloud computing together to solve policy problems,” Smetters says. The goal is to use big data to show how policy can shift more tangible numbers. For example, increasing deportation reduces both the GDP and employment, while legalizing undocumented workers has little impact.

Such massive data would strain traditional storage methods, and simulating policy combinations using traditional methods could take up to a day. With the help of cloud computing, every combination has been preloaded and stored, so that the model instantly shows thousands of projections.

In most cases, the model’s projections closely resemble those of the Congressional Budget Office. However, on Social Security, the PWBM projections vary slightly from those made by CBO and the Social Security Administration. The results are alarming—the model shows a faster and larger deterioration of the trust fund reserves. Burham calls the predictions “fairly surprising. When we run the numbers, we don’t really know what the outcome is going to be.” Burham points to the confusion surrounding Brexit in the U.K. as the perfect example of how the PWBM could be used by both elected officials and voters: “Maybe if there had been a model like this to forecast impacts of the Brexit vote, it could have influenced voters. Many people seem to be a little surprised at the aftereffects of their vote.”

Burham hopes the PWBM will eventually expand to show how different issues affect one another—toggle immigration metrics and you’ll see how those changes impact Social Security. How powerful could this tool become someday in translating virtual scenarios into real-life societal impact? Burham admits it has its limits: “It would give good information about the future effects of policies,” she says. “Even if it’s not quite godlike.”

Published as “Policy Playground” in the Fall 2016 issue of Wharton Magazine.