Entrepreneurship has become a thriving part of the Wharton education experience. Need proof? Consider the fact that Wharton’s Kartik Hosanagar hardly ever walks home alone.

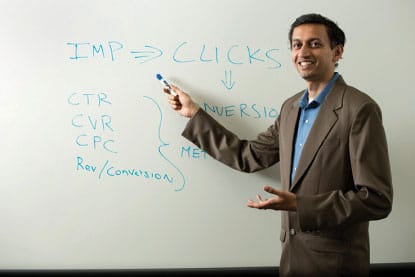

Hosanagar, an associate professor specializing in Internet commerce who co-founded his own Web company, is widely respected on campus as a patient mentor to budding entrepreneurs.

Kartik Hosanagar (Photo credit: Tommy Leonardi)

One of Hosanagar’s classes is called “Enabling Technologies.” Student assignments include taking a real-world business problem faced by a startup and then spending a week developing a solution to it. Hosanagar has taught the class for a decade, and the changes to the class during that time have mirrored the evolving nature of Wharton entrepreneurship teaching and research.

For one thing, enrollment in the course has exploded. It started with 55 in 2003; now, there’s not enough room to meet demand, despite the seven sections offered by two faculty members. Hosanagar’s office hours are booked solid with his own students.

The nature of students’ interests has changed too, Hosanagar says. Nearly all of them now are interested in starting companies. But that wasn’t the case when the class first began; back then, he says, most of his students were planning careers in investment banking and were taking the class simply to better understand how to value a startup company when they helped to acquire it.

With today’s students more interested in building companies than in buying them, “I don’t get that question too much any more,” he says.

Instead, students pitch their ideas—so many that they have broken free from the confines of his classroom or office hours.

Hosanagar has invited anyone at Penn who wants to discuss a business plan to join him at the end of the day as he walks the three miles from his Huntsman Hall office to his Society Hill home. Hosanagar’s walk-and-talk offer has, in the parlance of the Web, gone viral.

“I can’t remember the last time I didn’t have someone with me,” he says. “The amount of interest in entrepreneurship at Wharton is just crazy.”

The “crazy” interest observed by Hosanagar is part of a profound, if perhaps underappreciated, shift in some of the most basic elements of the culture of Wharton and its approach to a business education. Historically, the School has been associated with careers in finance and consultancy. But in the past decade, the business world has changed, and both Wharton and Wharton students have changed along with it.

A growing number are willing to trade wing tips, three-star Manhattan restaurants and Tribeca lofts for sneakers, take-out pizza and sleeping under their desks as they race to get a product out the door. Entrepreneurship, with its attendant risks and potential rewards, is emerging as a core element of the Wharton experience.

In some regards, this is nothing new. Entrepreneurship has been taught for decades at Wharton, though in the early years— the 1970s—the emphasis was more on what might today be considered “small business,” says Emily Cieri, managing director of Wharton Entrepreneurship. As the role of entrepreneurs in the modern economy advanced in the 1980s and 1990s, so, too, did the attention paid to it at Wharton. Today, says Cieri, the School’s commitment to entrepreneurship is realized through three different ways: research, teaching and co-curricular activities that encourage students to pursue real-world startup opportunities.

Much of the research occurs in the Sol C. Snider Entrepreneurial Research Center, endowed by Edward M. Snider, chairman of Comcast-Spectacor in honor of his father and led by Wharton’s Dhirubhai Ambani Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Ian MacMillan. Faculty members at the Center look into current issues connected to high-growth entrepreneurship, such as the role played by new technology or the effect that new financing arrangements or business models have on new-company formation.

Editor’s note: Watch a team win the Wharton Business Plan Competition:

Then, of course, there are classes. Curriculum development and teaching at Wharton are supported by the endowed Goergen Entrepreneurial Management Program. Entrepreneurship is available as a concentration for undergraduates and as a major for MBAs. Classes cover the gamut of general challenges that entrepreneurs are likely to encounter—financial, managerial, marketing and legal, among others. Other courses explore specialized areas, such as the increasingly popular field of socia entrepreneurship, for students interested in applying their business school skills to help bring about social change.

The third leg of the campus’s entrepreneurship efforts, co-curricular activities, may be stronger and more diverse at Wharton than at any other business school in the country, Cieri says.

The 15-year-old Wharton Business Plan competition typically gets about 150 entries from 400 students from across the University. Students submit written business plans and also pitch them live to judges drawn from the VC and founder community. Throughout the multiphase competition, everyone involved gets feedback; a total of $115,000 worth of cash and in-kind prizes also motivate. The $30,000 Perlman Prize, endowed by Ellen Hanson Perlman and Richard E. Perlman, W’68, goes to the top business plan. The most recent winner was ZenKars, an online automobile retailer co-founded by Jean- Mathieu Chabas and Venkat Jonnala, both WG’13.

| Show Us the Numbers

Wharton’s emphasis on entrepreneurship is made evident in any number of ways, including by choices that graduates make once they leave campus and move out into the real world. One trend is overwhelmingly clear: Students are developing a taste for entrepreneurship, with all its attendant risk-taking. Of the more than 800 graduates of the class of 2013, 59 launched their own companies. That’s double the number from just three years ago. In fact, more members of the Class of 2013 started a business than joined a hedge fund. Because the figure only counts full-time entrepreneurs, it understates Wharton graduates’ interest in the startup world. Wharton administrators say that in addition to founding companies, growing numbers of students are choosing to work as early employees at startups, as opposed to established firms. Because of the high failure rate of startups, that option can be just as risky as actually founding a company. Here are some other entrepreneurial-related data points to consider:

Maryellen Reilly Lamb, Wharton’s new deputy vice dean of admissions, financial aid and career management, also noted the School’s growing number of grants, competitions and special programs set up to help prospective entrepreneurs get a headstart. “If you have an idea or a business plan, Wharton is a great place to be,” she says. “You’ll find an incredible amount of support and enthusiasm.” —Lee Gomes |

Editor’s note: Wharton | San Francisco is positioned in the Bay Area for a reason. Full-time Philadelphia MBA students participate in Semester in San Francisco to take advantage of that proximity to Silicon Valley and immerse in the startup scene. Watch this year’s SiSF cohort in our latest video:

Wharton Entrepreneurship’s Venture Initiation Program is designed to resemble the incubators that are popular in technology hubs like Silicon Valley and Manhattan. The program is open to up to 35 student-run startup ventures; it offers them office space from which to work and the chance to build deeper mentor relationships with faculty members and visiting entrepreneurs, as well as to gain the support of other students in the program. A complementary program at Wharton | San Francisco supports up to 10 student-led ventures.

A related activity is the Entrepreneur in Residence mentoring program, which during the school year brings in successful entrepreneurs who hold “office hours,” meeting privately for a half-hour with students who want to ask questions about their own startup ideas.

Another resource is the Wharton Venture Award, which since 2006 has given as many as five grants of $10,000 annually to students with especially promising business plans. Recipients of the award are chosen by an alumni panel of VCs and entrepreneurs. The funding allows recipients to spend the summer building their startups, without having to worry about finding an unrelated, full-time internship in order to pay the bills.

Typical of this new breed of entrepreneurial-minded Wharton student is Betty Hsu, a second-year student who is finishing her MBA while also launching ProfessorWord, an edtech startup that helps students learn vocabulary in context as they read online.

Hsu says that after earning her bachelor’s degree at Harvard, she knew she wanted to continue with an MBA, but was unsure if Wharton would be right for her startup-oriented personality.

Betty Hsu (Photo credit: Colin Lenton)

“Of course, I knew Wharton’s reputation. It is a fantastic school,” she says. “I was a little apprehensive about how useful it would be for someone interested in a startup. But I discovered it is a great place for aspiring entrepreneurs. In fact, more and more of the students are like me. It’s changing the dynamic at Wharton a lot.”

Hsu says two classes were especially helpful to her entrepreneurship endeavors. In “Communication Challenges for Entrepreneurs,” small groups of students practiced startup pitches, benefitting from feedback not only from faculty, but also from visiting entrepreneurs. “Legal Aspects of Entrepreneurship,” she says, was useful in anticipating the legal issues involved with starting a company, especially “given that we don’t have money to be hiring lawyers.”

For Wharton faculty, this increasing emphasis on entrepreneurship is not without its challenges and begs the question: Can you even teach someone to be an entrepreneur?

Raffi Amit, the Robert B. Goergen Professor of Entrepreneurship and academic director of the Goergen Entrepreneurial Management Program, says that contrary to popular belief, entrepreneurs don’t as a group have very much in common. For every entrepreneur who is especially risk seeking or who possesses a deep knowledge of a particular industry, Amit says, there is another who is risk averse or who has only a passing knowledge of the business field he or she is entering.

Raffi Amit (Photo credit: Colin Lenton)

“There is no single trait, or even bundle of traits, that distinguishes successful from unsuccessful entrepreneurs,” he says.

Hence Wharton’s approach, which includes research into the basic structural patterns of the new entrepreneurial economy, along with a grounding in a cross-section of basic business skills, the sort that are useful in any business setting.

“Especially at a startup, you need to be a jack of all trades,” says Amit. “Things change very rapidly, and you have to be able to embrace change if you are going to survive. There is life after the startup phase of a company, and if you are going to be successful, you are going to need the sort of robust background that will help you think about running the company.”

Which is precisely why another entrepreneur chose to get an MBA at Wharton. Davis Smith, WG’11, G’11, co-founder at Baby.com.br, a parents-oriented e-commerce site in Brazil, recalls how he decided to attend Wharton only after making a win out of his first Web business, which involved pool tables.

“People thought I was crazy that I would go back to business school after already being a successful entrepreneur,” Smith says. “They told me that I should just take the money and use it to start my next company.

“But I saw it as an investment in myself. Wharton opened my mind to new ways of thinking, and exposed me to new ideas and new business models,” he says. “And it certainly helps with credibility. Some entrepreneurs criticize the MBA, but a lot of VCs have MBAs themselves and really respect the training.”

The entrepreneurial success of Robert Goergen, WG’62, has earned him respect far beyond Wharton’s Philadelphia campus. Starting in the 1970s, he took a small candle company and built it into Blyth Inc. Now one of the country’s biggest home products supplier, Blyth is a publicly traded company with 4,000 employees whose IPO created 25 millionaires. That latter fact, says Goergen, is one of the reasons he is such a strong supporter of entrepreneurs—at Wharton through the Wharton Goergen Entrepreneurial Management Program and beyond.

Robert Goergen

“Entrepreneurism is what creates jobs in this country,” he explains. “The big companies are usually firing people, because they are always looking for economies. But entrepreneurs, hopefully, create growth companies, and those in turn create jobs.”

Goergen makes a point of staying in touch with other alumni and with current students, becoming part of the extensive support network that is universally regarded as one of Wharton’s most important contribution to prospective entrepreneurs.

In the case of MentorTech Ventures, that support is formal; the outfit is a traditional venture capital firm, but one that works only with faculty, students and alumni from across Penn—not just Wharton.

Why a Penn-only VC firm? Because it works, says Michael B. Aronson, W’78, a serial entrepreneur himself before becoming managing director at MentorTech.

“I started my first company while an undergraduate, with my professor,” recalls Aronson. “The three other successful companies I started before my career as a venture capitalist had the same mix of Penn students, alumni and faculty. I recognized this as a successful strategy. There is a pretty extensive Penn network we are able to tap into.”

Among MentorTech’s greatest hits are Diapers.com, founded by Marc Lore, and sold to Amazon in 2010 for roughly $540 million, and Yodle, the Nathaniel Stevens, W’10-founded, profitable but still-private Web marketing firm currently with a thousand employees (which Hosanagar helped grow).

Much of the other networking at Wharton is the informal, old fashioned sort, involving relationships of mutual friendship and support that often last a lifetime.

“There is already a strong entrepreneurial community at Wharton, and it keeps getting stronger” says Wharton senior Evan Rosenbaum, who is currently putting the final touches on Layers, which allows authors to bring books to life on phones, tablets and computers with simple tools. “MBAs often have business experience, and they are always willing to talk about it with undergraduates. And a growing number of undergraduates have already started businesses of their own.”

Rosenbaum, who is president and founder of the Wharton Undergraduate Entrepreneurship Club, says his own company may be the best example of the power of Wharton’s extensive formal and informal entrepreneurship networks. While developing Layers, Rosenbaum participated in the Venture Initiation Program and received a Wharton Venture Award. Additionally, two of the company’s initial investors are alumni. The company is targeting independent authors as the first market it hopes to conquer, and its marquee client has a Wharton connection: Chris Maxwell, an adjunct professor of management and senior associate director of the Wharton Leadership Program. Maxwell is using the Layers platform to publish his next book on developing leadership skills.

“Layers simply wouldn’t exist without the Wharton network,” says Rosenbaum.

Layers already raised $750,000 in seed capital, a bit of early success that would come as no surprise to Hosanagar, who spends his evening “commutes” with students who want to follow the lead of Rosenbaum and others. During his evening walks with aspiring entrepreneurs, Hosanagar says, he finds that most of the business plans he hears about are sound ones.

“There is no dearth of good ideas,” he says. “The next step is execution.”